The debut authors featured in our third annual 5 Over 50 have all demonstrated the patience and resilience that is required of anyone who is devoted to writing as a lifelong art. What makes them special is not simply the quality of their first books, but also that they’ve already achieved so much, including obtaining the wisdom and perspective that comes from living a bit of one’s life.

In our November/December 2018 print issue you can read essays by each of these five authors about their paths to publication—as well as the inspirations, obstacles, and truths they discovered along the way—and below you can read excerpts from each of their debut books.

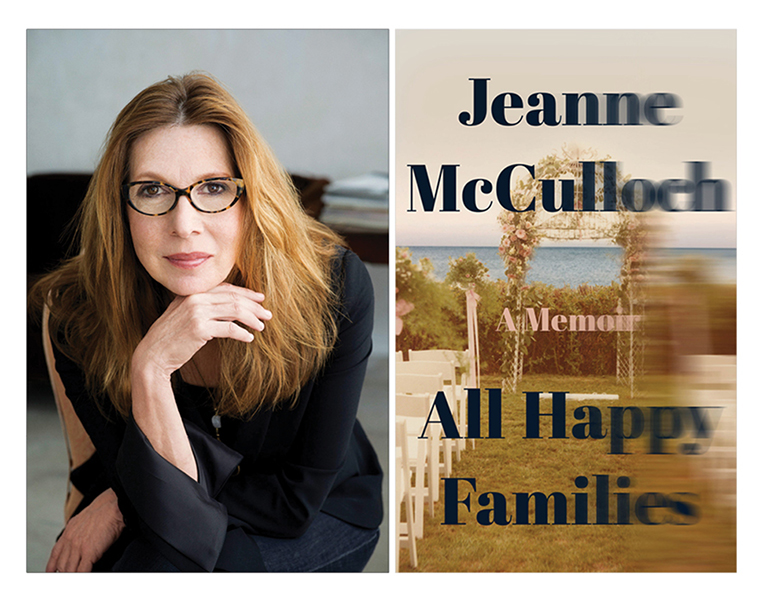

All Happy Families (Harper Wave) by Jeanne McCulloch

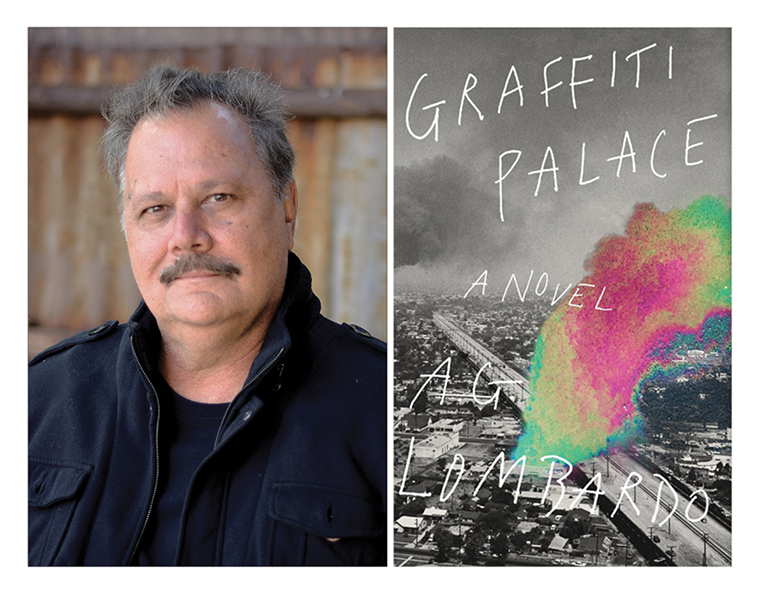

Graffiti Palace (MCD Books) by A. G. Lombardo

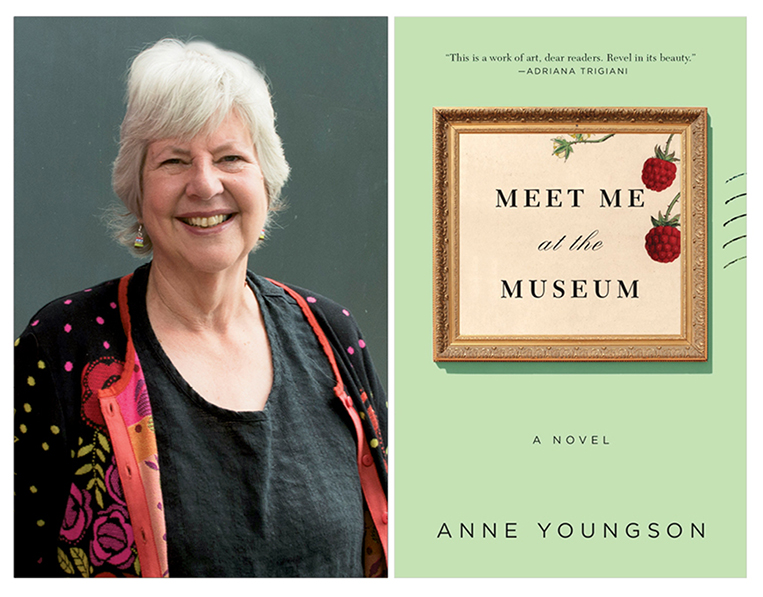

Meet Me at the Museum (Flatiron Books) by Anne Youngson

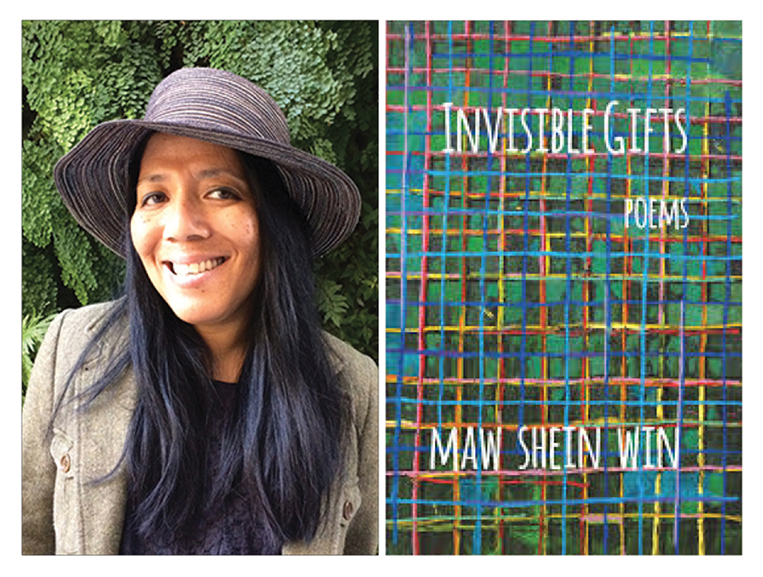

Invisible Gifts (Manic D Press) by Maw Shein Win

For Single Mothers Working as Train Conductors (University of Iowa Press) by Laura Esther Wolfson

mccullogh_grid.jpg

Jeanne McCulloch, author of All Happy Families, published in August by Harper Wave.

Part I

August 1983

A woman walks into the sea. It’s a mid-August day. Early morning. The sky is clear. A mid-August day on the beach near the end of Long Island and it’s the summer of 1983. Seagulls idle on the wet sand, and far out the fishing boats from Montauk patrol, small as dark toys against the horizon. It’s a perfect late-summer day. The woman on the shore is my mother. She wears the iconic headdress of her era, a floral bathing cap with brightly colored petals. She walks cautiously, hands out for balance, because even in a calm surf you can’t be too careful walking into the sea. She always taught us that. Respect for the sea. The latex petals of the cap flutter about her head, almost festive as she moves. It’s early morning and my mother walks into the sea. Behind her is our house, a long, gray, sea-weathered Clapboard house, stretching along a sand dune like a giant sleeping cat. My father bought this house years before the area became known as the Hamptons—back when it was still considered a long way from New York City, known mainly for artists and potato fields and the fisherman who made their living trawling off Montauk Point. The house had a shabby grandeur to it that time forgot. No air-conditioning (“The sea is our air conditioner!” my mother would proclaim) and no pool (“The sea is our pool”).

Every August when I was young, it was a giant slumber party in the house by the sea. My sisters and I would fall asleep against a tumble of cousins in quilts, listening to the steady refrain of waves gliding along the shore—the moonlight outside our bedroom spackling a silver route to the horizon.

August 13, 1983, was the day of my wedding. I was twenty-five, a messy splatter of freckles across my nose the final badge of childhood. Just before sunset that afternoon, I would put on a vintage lace dress that swooped gently off the shoulder in a style I saw as reminiscent of Sophia Loren in her glory days and my mother saw as suggestive of the sale rack at a yard sale. In the house that morning, they were talking in various rooms. In the pantry, the boy delivering flowers, sprays of lilies of the valley and a basket of rose petals for the wedding cake, was being bossed around by Johanna, the Irish cook. Johanna never got to boss anybody in the household; everyone, the housekeeper, the gardener, everyone disregarded her. She was a small woman in a hairnet, whose wisps of dry black hair nevertheless escaped and were often found floating in the vichyssoise. She stamped her foot, a white orthopedic shoe. “Get out of my kitchen,” she was telling the delivery boy from the florist’s shop, “I’m too busy,” she scolded him. “Go.”

In the sunroom, my half-brothers, three men in their early forties, sons from my father’s first marriage, huddled in conversation. They all had beards and ready laughs; they—in addition to my half-sister—had come for the wedding with their spouses and their children from the far flung places where they lived lives of their own. Half siblings, and the term was apt; I half knew them, and I half didn’t. Scott raised llamas in New Mexico; in Florida Keith painted lush floral landscapes, some with naked women; in Colorado, Rod was engaged in investment strategies for a business no one understood. Mary Elizabeth, called MB, was an Arabic scholar in Paris. In my father’s sunroom, the morning light angled across the sisal rug, dust motes played in the air, and my three half-brothers were talking together, shoulders hunched, coffee mugs in hand.

The gardener, Vincent, in yellow protective earmuffs and a fishing cap, drove his seated mower in even rows up and down the sloping lawn, as he did every morning of summer, this day steering around the large white party tent erected earlier in the week for the reception. My wedding was scheduled to take place at five in the afternoon. It had been timed and debated for months, the proper moment for a wedding. The ceremony was to be situated by the garden up by the house, with a view giving out to the sea. “Situated”—that was the term used by Ruth Ann Middleton, the professional wedding planner my mother had hired to marshal the wedding to perfection. A white wire gazebo has been placed there, and the florist would wreath the lattice in garlands of pink roses. Five in the afternoon was the time the light would be the rich gold particular to late summer. A bagpiper in a kilt had been hired by my mother, so at the ceremony’s conclusion, he’d guide the guests from the garden down to the tent—braying the union of husband and wife as the setting sun burnished rose through the trees.

“You know, men in kilts don’t wear any underwear,” my half-brother Keith had told us the day before the wedding, as we drove to visit our father. “Seriously, not a stitch. Just a pink ribbon tied around the big fella.” My siblings and I were in the family station wagon when he told us that, on our way to Southampton Hospital. Our father lay in a coma in the ICU, having had a massive stroke two days before the wedding, leaving our home for what we suspected might be the last time strapped to an ambulance stretcher—the strap a thin, final harness to our life. He had had the stroke following an abrupt withdrawal from alcohol after a lifetime of drinking, having gone cold turkey at my mother’s insistence so—in her words—he’d “sober up” for the wedding.

On the way to the hospital, Scott had insisted we stop at the fried-chicken place off Route 27, in case we got hungry, and as we stood watching our father breathe, the bucket of chicken sat unopened at the nurse’s station of the ICU, filling the air with its irrelevant fragrance.

We had bowed to my mother’s insistence that the wedding should go forward, despite our father’s condition. Because, she claimed, it’s what Daddy would want. “Besides,” she added, “all my friends are already en route.” And so a man with no underwear, in a plaid skirt, was going to bray on our front lawn at sunset as my father lay in a coma over in the next town.

The morning of my wedding, an easy breeze blew down the beach. My teenage nephews sat on their surfboards just beyond the break. All was calm and serene from the lilting vantage point of the sea. Occasionally a swell would captivate them and they angled their boards toward the shore, riding in on elegant curls of foam.

Later that afternoon, my mother would pin the family veil on my head. She’d mutter about how I should have let her get a proper hairdresser to tame my wild beach hair. Then she’d call the hospital and instruct them that no matter what happened that evening to her husband, they were not to call our house. Because, she’d go on to say, we were having a party.

The morning of August 13, 1983, the day settled into a steady rhythm near the tip of Long Island. Taking her swim before breakfast, which, she believed, was de rigueur in summertime, my mother walked into the sea.

From All Happy Families by Jeanne McCulloch. Copyright © 2018 by Jeanne McCulloch. Published by Harper Wave, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission by the publisher.