Each year a lot of attention is paid to “new and emerging” authors under a certain age. Every fall the National Book Foundation honors a group of authors through its 5 Under 35 program, designed to introduce “the next generation” of fiction writers. And in the spring the New York Public Library offers its ten-thousand-dollar Young Lions Fiction Award to a writer age thirty-five or younger. Yale University Press only recently lifted the age restriction for the legendary Yale Series of Younger Poets, which for nearly a century stipulated that the publication award was open only to poets under forty. Every ten years the London-based literary magazine Granta names the twenty writers it considers the Best of Young British Novelists, all of them under forty. The New Yorker made waves back in 1999 with its first 20 Under 40 list—a popular feature the magazine repeated in 2010—anointing authors such as Michael Chabon, Junot Díaz, Jhumpa Lahiri, Sherman Alexie, Edwidge Danticat, and George Saunders as “standouts in the diverse and expansive panorama of contemporary fiction,” as the New Yorker’s fiction editor Deborah Treisman put it. BuzzFeed got in on that action with a feature in 2014, “20 Under 40 Debut Writers You Need to Be Reading,” that included the line: “Out with the old, in with the debut.”

While there is something undeniably exciting about news of the next big book by an undiscovered talent, we would like to remind writers and readers that new does not necessarily mean young, no matter how broadly that qualifier is defined. And while popular culture tends to favor youth, there is something equally exciting about the work of those authors who have lived more than half a century—some pursuing alternative careers, others raising families; all of them taking their time, either by choice or by necessity, and collecting valuable life experience that undoubtedly informs and inspires their writing—before publishing a book.

Here, in their own words, we present five authors over the age of fifty whose debut books were published in the past year.

Know the Mother (Wayne State University Press, March) by Desiree Cooper

Her, Infinite (New Issues Poetry & Prose, March) by Sawnie Morris

An Honorable Man (Emily Bestler Books, April) by Paul Vidich

You May See A Stranger (TriQuarterly Books, May) by Paula Whyman

Rust Belt Boy: Stories of an American Childhood (Bauhan Publishing, May) by Paul Hertneky

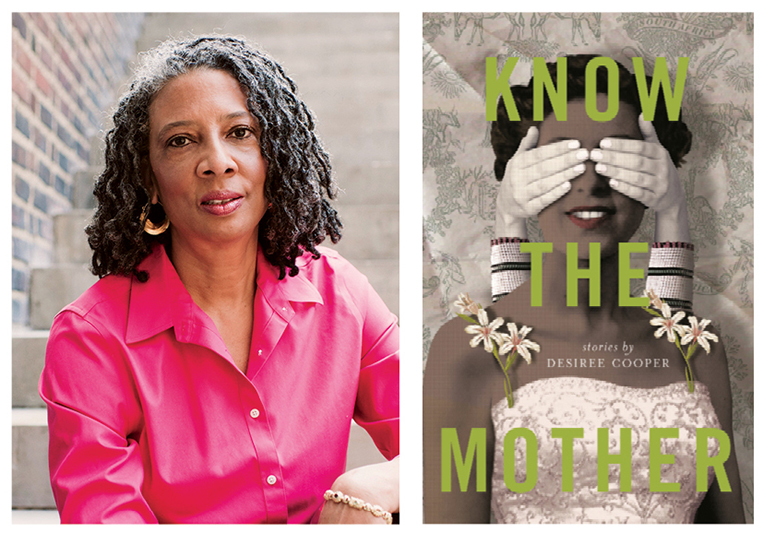

Desiree Cooper

Age: 56

Residence: Detroit, Michigan

Book: Know the Mother, a collection of meditative stories exploring the complex archetype of the mother in all of her incarnations.

Publisher: Wayne State University Press (March)

Agent: None

cooper_online_2.jpg

Twenty years ago I was deep in the throes of raising two elementary-schoolers and struggling to keep apace with the demands of motherhood, wifehood, and personhood. I had a career as a newspaper columnist, which I accomplished between drop-offs and pickups, sometimes driving three hours one way to deliver kids to tutors or games or piano lessons.

Once a year I landed on the shores of a poetry residency where I was a board member (not an actual poet), feeling like a bedraggled refugee. It was there, in the late 1990s, that I penned a poem titled “Know the Mother.” It was a narrative poem about a daughter sitting by her mother’s deathbed, realizing that she will never know who her mother really was. I remember thinking, even then, “If I ever have a book, that will be the title.”

In March 2016, five days before my fifty-sixth birthday, I stood in front of a packed Detroit art gallery for the launch of my first book, a collection of flash fiction titled Know the Mother. By then I was a grandmother, a Kresge Artist Fellow, and a survivor of what could have been a fatal encounter with a semitruck only months before.

All I could think was, “I can’t believe I lived to see this moment.”

Since the age of four, I have wanted only to write stories. But as part of the first generation after the civil rights movement and the oldest child of middle-class strivers, I quickly learned to think of writing as a hobby, not a “real job.” The currents of life sent me on a traditional path to college, law school, a career in journalism, marriage, and family. Through it all, I was a mare champing at the muse. I wrote for myself, on the side, in writing groups, at retreats. I found a community of kitchen-table writers who helped shape my voice. Frustrated at the stingy moments left for me to write, I often very nearly stopped, but I couldn’t stay away for long. Somehow I managed to believe in myself as a creative writer with little outward validation.

Then, one day while I was lurking at a writing event, M. L. Liebler, one of Detroit’s well-known authors and indefatigable writing mentors, shouted “Send me your book!” when he saw me in the parking lot. My heart stopped and I looked around, wondering who he was addressing. He had heard me read at an event and assumed I had more. I had been outed.

Liebler liked my work and handed it to Wayne State University Press. When the gifted editors at the press and the brilliant publicist Kima Jones both said that they would get behind my manuscript, I was awash in disbelief. Maybe because, deep down, I had resigned myself to being a secret writer forever.

I would be lying to myself if I didn’t admit that the path to my first book was as lucky as it was labored. But there were forces that prepared me to step through the publishing door when it miraculously opened late in life. My career as a newspaper columnist gave me the muscle for compressed storytelling, a skill that shaped my ability to write flash fiction. I never stopped sharing my writing with other writers and readers. They became my community MFA program, teaching me what works and what doesn’t, forcing me to produce, encouraging me to stretch.

My life as a mother gave me fodder, empathy, and insight into the human condition. It taught me patience that I never knew I could muster, and a concrete understanding that, while time often feels like a foe, it can be a friend as well. The women in my collection are informed by my own experiences—and those of the women I have met along the way. They are born out of a lifetime of living and observing how racism and sexism profoundly affect our intimate lives.

When I was in my thirties I dreamed of writing a book called Know the Mother. But it wasn’t until I was fifty that I knew for sure who she really was.

(Photo credit: Justin Milhouse)