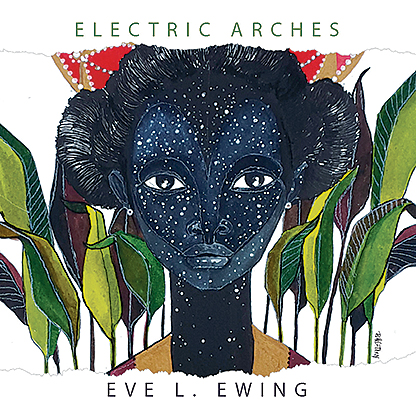

The ten poetry collections featured in our thirteenth annual roundup of debut poets offer a glimpse of the wide range of contemporary poetry. Each of the books, published in 2017, shows just how much poetry can do. Eve L. Ewing’s Electric Arches tells stories that reckon with history and imagine a better future, while Layli Long Soldier’s WHEREAS and sam sax’s Madness reclaim language that has been distorted by governments and institutions of power. Emily Skillings’s Fort Not reveals the tendencies of our culture and society through the trappings of modern life, as does Chen Chen’s When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities. Kaveh Akbar’s Calling a Wolf a Wolf and Jenny Johnson’s In Full Velvet both give voice to the interior—Akbar to the ongoing work of faith, Johnson to the vagaries of the heart and desire. Joseph Rios’s Shadowboxing and Airea D. Matthews’s Simulacra create personas and alter egos that argue and spar with one another, while William Brewer’s I Know Your Kind clears a path for understanding others. And all ten collections do what poetry does best: inhabit the many possibilities of language and form as well as attend to, as Seamus Heaney put it, “the lift and frolic of the words in themselves.”

We asked the poets to share the stories and influences behind their books, and they responded with a list of inspirations as varied as their collections, from the food of April Bloomfield and music of Flying Lotus to the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein and words of Adrienne Rich. When we asked the poets to offer advice to writers who are stuck or looking to publish their first book, however, their answers coalesced around some common suggestions: Take a break when you’re struggling with a piece. Permit yourself to write one or two or thirty or a hundred lousy poems. Most of all, reach out to the people who can keep you afloat. Listen to your family’s stories, as Chen and sax do, or talk with your kids, as Matthews advises. Or, as Johnson and Rios suggest, call up your friends, encourage one another, and then hold one another accountable for getting the work done.

Writing poetry can often feel lonely or frustrating or even futile—especially during a year of political turmoil and soul-searching—and these poets remind us to turn to whatever will protect our capacity for wonder and allow each of us to be our “whole self on the page,” as Rios says. They remind us to be attentive to the world, and they urge us to be ready for whatever scrap of language or feeling might help us pass from silence into speaking and jolt a poem into being.

Kaveh Akbar | Airea D. Matthews

William Brewer | Chen Chen

Eve L. Ewing | Jenny Johnson

sam sax | Emily Skillings

Joseph Rios | Layli Long Soldier

h1703162.jpg

Kaveh Akbar

Calling a Wolf a Wolf

Alice James Books

I try not to think of God as a debt to luck

but for years I consumed nothing

that did not harm me

and still I lived, witless

as a bird flying over state lines.

—from “Personal Inventory: Fearless (Temporis Fila)”

How it began: When I got sober, poetry became my life raft. Every poem in Calling a Wolf a Wolf was written from a few months to a few years after I got sober. I had no idea what to do with myself, what to do with my physical body or my time. I had no relationship to any kind of living that wasn’t predicated on the pursuit of narcotic experience. In a very real way, sobriety sublimated one set of addictions (narcotic) into another (poetic). The obsessiveness, the compulsivity, is exactly the same. All I ever want to do today is write poems, read poems, talk about poems. But this new obsession is much more fun (and much easier on my physiological/psychological/spiritual self ).

Inspiration: The searching earnestness of the people I’ve met in recovery. They’ve taught me how to talk about myself without mythologizing, without casting myself as some misunderstood hero maligned by the world. I think (hope!) that resistance to flattening my narrative into some easy self-serving hero’s journey is one of the central features of Calling a Wolf a Wolf.

Influences: Franz Wright, Abbas Kiarostami, Mary Ruefle, Kazim Ali, Daniel Johnston, Ellen Bryant Voigt, Carl Phillips, Brigit Pegeen Kelly, Nicholson Baker, Dan Barden, Kathy Acker, all writers for The Simpsons from 1990–1999, Fanny Howe, Eduardo C. Corral, Jean Valentine, francine j. harris, the verve of Marc Bolan, the voice of Kate Bush, the sneer of Justin Pearson/The Locust, the frequency of Eric Bemberger’s guitar, Sohrab Sepehri, Russell Edson, Lydia Lunch, Zbigniew Herbert, Joanna Newsom, Heather Christle, Patricia Smith, Anne Carson, Robert Olen Butler, Bruce Nauman’s neon art, Vic Ketchman, my mother.

Writer’s block remedy: I don’t really believe in writer’s block. If I sit down to write in earnest and give myself enough time, eventually I’ll walk away with something. Even if it turns out to be nothing (which is usually the case), I’m still training and preparing my instincts for the next poem. Even bad poems that go nowhere provide compost for the good ones to come. That said, I do believe in refractory periods, periods spent rebuilding one’s relationship with silence. Ellen Bryant Voigt talks about how in order to strike, a cobra also needs to recoil. I have recoil periods in which I throw myself into my reading, a kind of active listening. So much of Calling a Wolf a Wolf works by hypersaturation, by these breathless rushes of language. It’s been immensely useful for me to go back into silence, to reclaim a bit of psychic quiet to take back into the poems.

Advice: Be kind to yourself and to other poets. There are so many people in the world who would conspire against our joy, who would mistake our reverent wonder for idleness. Against everything, we have to protect our permeability to wonder. That’s the nucleus around which all interesting art orbits.

Finding time to write: I’m one of those people who wakes up obnoxiously early to get in my hours before the world really starts up. I like to get into my poem-writing while my brain is still gummy with dream logic, before the mundane argle-bargle of the everyday comes in.

What’s next: Rebuilding a relationship with silence. Being the best professor and mentor I can be. Orienting myself toward gratitude despite a political moment working very hard to prevent that. Being in love and planning a wedding. Being an uncle. Touring with the book. Staying alive one day at a time.

h1703163.jpg [1]

Age: 28.

Hometown: Not sure exactly—I was born in Tehran, Iran, then moved to Pennsylvania, to New Jersey, to Wisconsin, to Indiana, to Florida, and now back to Indiana.

Residence: Lafayette, Indiana.

Job: I teach in the MFA program at Purdue University.

Time spent writing the book: The honest answer is twenty-eight years, maybe even longer than that, but to answer the question I think you’re actually asking, the oldest recognizable poem in the book is about five years old. That’s fairly fast, actually. There are a number phrases and images I cannibalized from poems much, much older than that, though.

Time spent finding a home for it: Not very long. Carey Salerno, my editor at Alice James, saw a poem of mine published by the Poetry Society of America and wrote to me asking if I had a manuscript. I actually wasn’t really done with Calling a Wolf a Wolf yet, but I sent her what I had with the caveat that I still needed time to continue building and rearranging and reimagining. She liked what she saw and took the leap. I couldn’t imagine working with a smarter, more generous, more compassionate editor. So much of what is good about the book is the result of her patient guidance and mentorship.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: Nicole Sealey’s Ordinary Beast (Ecco) is a collection I think people will still be reading in fifty years. Javier Zamora’s Unaccompanied (Copper Canyon Press). William Brewer’s I Know Your Kind (Milkweed Editions). Airea D. Matthews’s Simulacra (Yale University Press). Cortney Lamar Charleston’s Telepathologies (Saturnalia Books). Safia Elhillo’s The January Children (University of Nebraska Press). Layli Long Soldier’s WHEREAS (Graywolf Press). Eve L. Ewing’s Electric Arches (Haymarket Books).

***

h1703164.jpg [3]

Airea D. Matthews

Simulacra

Yale University Press (Yale Series of Younger Poets)

but I knew it was a winged thing,

a puncture, a black and wicked door.

—from “Rebel Prelude”

How it began: My life and the lives of the people who have affected me were the impetus for the book. I’d had undiagnosed mental illness for a very long time, and I wanted to get to the root of it. It started with a question, actually. I asked myself if I had inherited hunger and instability. As I wrote the book, the universe handed me small parts of a very complicated answer.

Inspiration: Books, people, and technology—Roland Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse, Ludwig Wittgenstein’s The Blue and Brown Books, Albert Camus’s The Stranger and The Rebel, Franz Kafka’s absurdity, Greek and Sumerian myths, the wit of Twitter and Facebook, the days of Motorola Q, Anne Sexton, Gertrude Stein, my family and friends. In short, everyday life—private and public.

Influences: Aside from the nods in Simulacra to my poetic lineage, Nora Chassler, Vievee Francis, Rachel McKibbens, and Ladan Osman are some of my greatest artistic inspirations. They’ve all taught me more about community, poetry, and history through their generosity and friendship than I could ever hope to learn in a book. As literary exemplars, I’d have to say Rita Dove, Simone De Beauvoir, Anne Carson, Alice Notley, Haruki Murakami, Samuel Beckett, Italo Calvino, Muriel Rukeyser, Marina Tsvetaeva, Carl Phillips, Louise Glück, Antonio Porchia, Cecília Meireles, Wisława Szymborska, Heraclitus, Rainer Maria Rilke, Robert Hayden, and Zora Neale Hurston.

Writer’s block remedy: When I lose language it’s almost entirely because I am too focused on myself at that moment. And so, I step back. I consciously get outside of myself by unplugging and planting myself in public spaces at odd hours of the day. My perspective shifts because, in public, my gaze moves toward other forms of subjectivity—nature, outside conversations, cityscapes, etc. I am also a big fan of stepping away from work to listen to my kids’ observations about life and/or ask them how they’d work through a problem. Young souls are closer to Edenic wisdom. They understand human nature and the journey in a way that seems to elude the more grizzled traveler.

Advice: Listen to yourself, your hand, your gut, your pen, your mind. Be authentically who you are as a writer. Your work has its own logic and its own tools; honor them. And, finally, wear comfortable shoes because the journey toward making the impossible possible is rugged, long, and lovely.

Finding time to write: I suppose I don’t find time as much as I make time. I have long practiced jotting down at least one observation every day—anything from watching a child play to documenting arguments. I find that those observations help me sustain focus when I sit to write in longer form.

What’s next: I am trying to gain fluency in my body’s primitive language, my instincts. The next collection, “under/class,” will be driven entirely by those instincts and will almost definitely be outside of definition and genre—social criticism, poetry, and short stories.

h1703165.jpg [4]

Age: 45.

Hometown: I grew up in Trenton, but I spent twenty years in Detroit. Detroit is the place where I matured into a writer.

Residence: The City of Brotherly Love (and car horns), Philadelphia.

Job: Assistant professor of creative writing at Bryn Mawr College. The college was voted one of the most beautiful campuses in the country (and not just the grounds); the people are exceptional humans.

Time spent writing the book: The poems were in my body my whole life, perceiving and altering the way I interacted with the world. Somatically, I would say it took me forty-plus years. But, in a more linear view, it took a solid five years to commit them to paper and have them coalesce into a collection.

Time spent finding a home for it: I heard “no” and “not quite right” so often, I started to answer to them. Interestingly, I had a hard time getting individual poems published, which explains why my publishing acknowledgements are fairly lean in the book. I sent the manuscript out thirty times in some form or fashion, under two different titles. It was rejected twenty-eight times. It was accepted twice, and I went with Yale.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: ALL OF THEM! It’s hard to name only a few, but here’s my feeble attempt: Kaveh Akbar’s Calling a Wolf a Wolf, Ife-Chudeni A. Oputa’s Rummage (Little A), Chelsea Dingman’s Thaw (University of Georgia Press), Layli Long Soldier’s WHEREAS, sam sax’s Madness, Nicole Sealey’s Ordinary Beast, and Charif Shanahan’s Into Each Room We Enter Without Knowing (Southern Illinois University Press).