For the past nine years 5 Over 50 has featured authors who published their debut books later in life, authors who prudently used the fertile soil of their life journeys to produce works of poetry and prose that benefitted from their having moved through what one such writer, Deborah Jackson Taffa, calls the potential “callowness of youth” and into a space of patience, trust, experience, and healing. The following debut authors over the age of fifty share stories of listening to an inner voice urging them to be a writer, having a natural disaster bring them back to poetry, falling asleep with a pen in hand every night, honoring and exploring their inner child to the fullest, and coming back to the radiant energy of a manuscript shelved for years. “This is the point where you feel assured to bet on yourself,” Dorsía Smith Silva affirms. Below are excerpts from this year’s five debut books; read essays by the authors in the November/December 2024 issue.

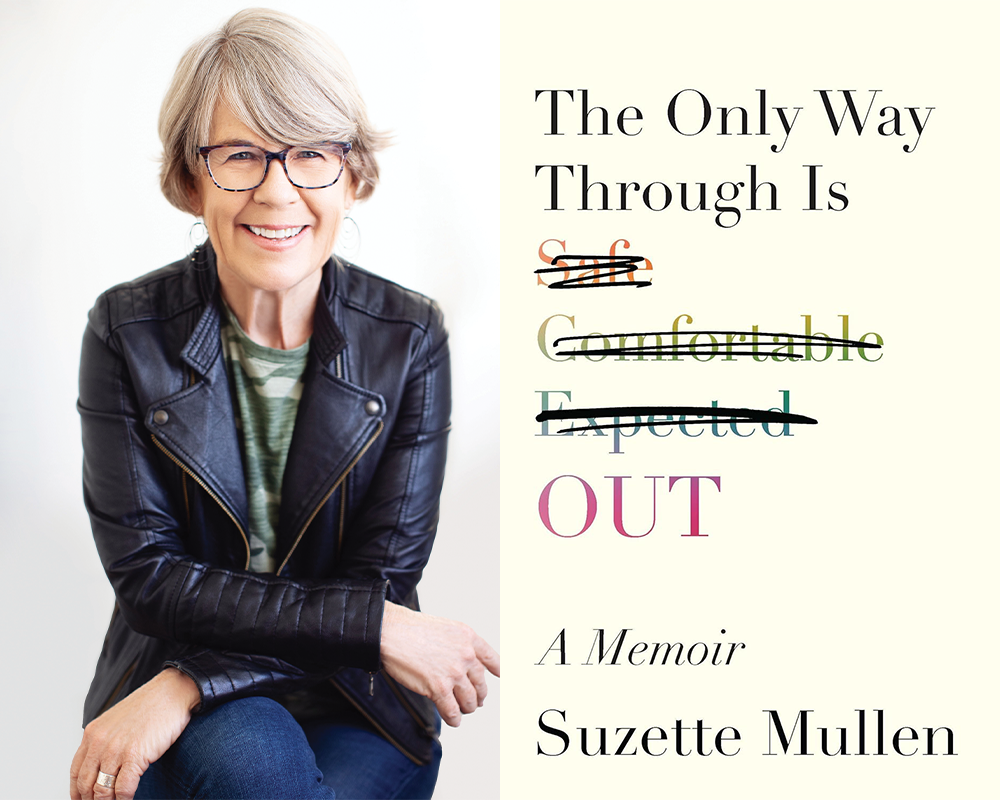

Suzette Mullen, author of The Only Way Through Is Out (University of Wisconsin Press)

Dorsía Smith Silva, author of In Inheritance of Drowning (CavanKerry Press)

Uchenna Awoke, author of The Liquid Eye of a Moon (Catapult)

Deborah Jackson Taffa, author of Whiskey Tender (Harper)

Parul Kapur, author of Inside the Mirror (University of Nebraska Press)

![]()

Suzette Mullen

Age: 63. Residence: Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Book: The Only Way Through Is Out (University of Wisconsin Press, February 2024), a memoir about awakening to one’s queerness later in life, coming to terms with deep-seated and decades-long desire, and risking it all to move through the world authentically, in previously unspeakable ways. Agent: None. Editors: Nathan MacBrien and Holly McArthur.

suzette_mullen.png

“I don’t know what to do with these feelings,” I said to Alice, my therapist, after I told her that I realized I was in love with Reenie, my best friend. “Should I tell Reenie? It feels dishonest to keep this from her.”

“You don’t have to share every thought you have. It’s not dishonest to keep a zone of privacy,” Alice said.

I’d never thought about a zone of privacy, but wasn’t that exactly what I’d been maintaining all these years, living one life in my head and the other out in the world? “But what if I’m actually gay? What am I supposed to do then?”

“So what if you are gay?” Alice said. “You don’t have to do anything about it. You’ve made a choice to live a certain lifestyle, and if you’re happy with it, you don’t have to change.”

I closed my eyes and smiled. It didn’t matter whether I was gay or not. I didn’t have to do anything about it. Nothing had to change.

![]()

Evan, my husband, and I watched the Houston Astros at Minute Maid Park. A middle-aged woman in the row in front of us put her arm around another woman.

Were they a couple? I couldn’t take my eyes off them. Gentle touches to the thigh, an arm being patted. A brush of the lips. They were a couple. My body ached.

I wanted to sit with my arm around Reenie at a baseball game. I wanted to kiss her lips. I wanted to touch her thigh.

That was never going to happen. Not now. Not ever.

I have a good life. I love my husband. I don’t have to change anything.

Evan and I saw Hamilton the first month it opened on Broadway. Cheered the Astros at Yankee Stadium with our sons. Picnicked on cheese and bread from Zabar’s and sipped North Fork sauvignon blanc in Central Park.

Evan snapped a photo of me, supine on the lawn, plastic cup in hand, the sun hitting me just so.

Perfect summer night, I posted on Facebook.

My perfect life received lots and lots of likes.

After the picnic, we made our way to the band shell area, already packed with people, mostly younger than us, and settled into a spot close to the stage, behind a metal barrier. But the stage wasn’t where my eyes spent most of the night. They kept returning to two young couples on the other side of the fence. Women in sundresses rubbing each other’s backs, playfully kissing each other, swaying to the music. Did Evan notice them too? Did he know Ingrid Michaelson had a huge lesbian following, a fact I discovered when I Googled her after we returned home?

What I would have given to sway freely on that side of the fence, to have my whole life ahead of me, to satisfy this longing that wasn’t going away. But I was with my husband, a kind and loyal man who loved me. Where the world said I should be and where I had chosen to be.

“Isn’t this great,” Evan said, putting his arm around me.

I put my arm around him. Stop this, I silently scolded myself.

We went to see the Broadway musical Fun Home. The show had many poignant moments—a young girl singing about her attraction to a woman with short hair and a ring of keys on her dungarees. A thirtysomething drawing cartoons to make sense of her life. A college freshman, her hand on the doorknob, staring at a sign about a gay and lesbian support group.

“Please, God, don’t let me be a lesbian,” she pleaded.

I wiped a tear from my cheek, hoping Evan didn’t notice. I didn’t want to be a lesbian either. Because if that’s what I was, how could I stay in my marriage? And how could I possibly leave? It was much easier to keep acting as if nothing had to change.

From The Only Way Through Is Out by Suzette Mullen. Reprinted by permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. © 2024 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved.

Author photo: Ashleigh Taylor