For our twenty-fourth annual roundup of the summer’s best debut fiction, we asked five writers to introduce this year’s group of debut authors. Read the July/August 2024 issue of the magazine for interviews between ’Pemi Aguda and Laura van den Berg, Jiaming Tang and Jessamine Chan, Michael Deagler and Akil Kumarasamy, Yasmin Zaher and Ayşegül Savaş, and Gina María Balibrera and Julie Buntin. But first, check out these exclusive readings and excerpts from their debut books.

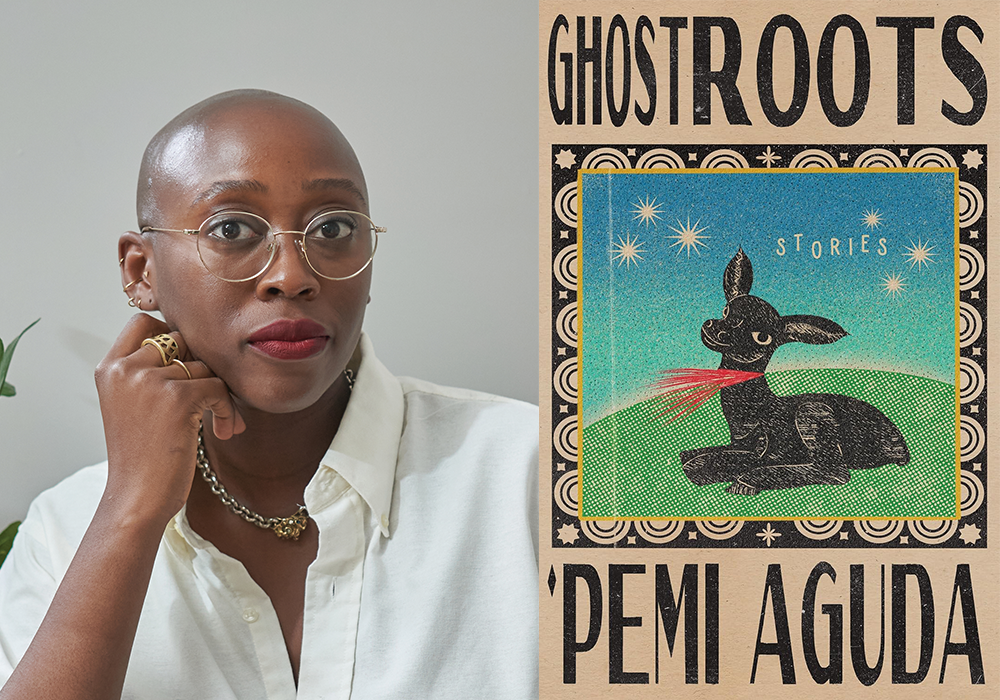

Ghostroots (Norton, May) by ’Pemi Aguda

Cinema Love (Dutton, May) by Jiaming Tang

Early Sobrieties (Astra House, May) by Michael Deagler

The Coin (Catapult, July) by Yasmin Zaher

The Volcano Daughters (Pantheon, August) by Gina María Balibrera

Ghostroots

’Pemi Aguda

pemi_aguda_-_ghostroots.png

’Pemi Aguda, whose debut story collection, Ghostroots, was published by W. W. Norton in May. (Credit: IfeOluwa Nihinlola)

Children can be cruel, you know?

![]()

The first man stands at the bedside of his sweating wife. He is watching their baby emerge from inside her. What he does not know is that he is watching their son destroy her insides, shredding, making sure there will be no others to follow. This man’s wife is screaming and screaming, and the sound gives the man a headache, electric like lightning, striking the middle of his forehead. He reaches out to hold her hand, to remind her of his presence. But he is surprised by the power of her latch, this strength born of pain, the way she crushes the bones of his fingers. He has to bite down to prevent himself from crying out.

And here is the baby, bloody and outside for the first time. The first man flinches at the sudden appearance of white eyeballs in the midst of the slimy red of birth.

“Um,” the doctor says, frowning. “You have a son.”

The first man leans down to catch the mumbled words from his wife’s mouth. “Yes, hon. He’s alive,” he reassures her. The whites of the baby’s eyes are imprinted in his mind, behind the headache, like an image from the past, blurred and clouded by time. He looks up to the doctor, who is still holding onto the baby, brows furrowed. “He’s alive, right, doctor? Is everything fine? Isn’t he supposed to cry?”

The doctor looks everywhere but at the first man. They fuss around, the doctor and the nurses, snipping, cleaning, moving.

“Doctor?” the man prompts.

“Mr. Man, you have a son! Congratulations! A living, breathing boy!”

![]()

The second man huffs beneath the weight of his wife. The Ikeja General Hospital has sent them home even though his wife is still bleeding from the birth. “Sorry, no space,” the head nurse told him, her attention moving so easily to the next patient. “Take her home; everybody bleeds.”

The second man’s mother holds open the door to their apartment, cradling the baby like an expert. She trails them to the bedroom, where the man gently lowers his wife to their bed—still messy with signs of frantic packing for the hospital. Once his arms are free, the mother transfers the baby to him, as if she has been waiting to rid herself of the infant.

“Maami,” he starts to say, but his mother leaves the room.

The baby is sleeping and his eyeballs move around beneath his thin lids. The second man is repulsed by this movement, this unconscious shifting, like a buried thing digging its way up. The man is then discomfited by this reaction to his child. He deposits his new son in the cradle that smells like wood polish, then goes to find his mother in the kitchen.

“Maami, will you make black soup for her? Will that help?”

The mother is staring out the kitchen window, her fingers steeping in a bowl of uncleaned tilapia. “That baby is not yours, I’m sure of it.”

“Maami, please. Don’t start this rubbish again.”

“That baby is not yours; I can swear on it! I know it. I feel it.” Her hands move again, lifting a gill flap, gutting the fish with a soft snap.

![]()

The third man walks into the dining room to find his wife dozing off while their baby quietly suckles at the feeding bottle’s nib. The image he encounters is this: her neck tilted backward and to the side so that the muscles seem contorted unnaturally, the tendons and veins pushing against skin. For a moment, he is sure she is dead.

She jerks awake when he tries to lift their son from her arms. Her hands instinctively tighten, then loosen. “Thanks,” she whispers, her eyes drifting to close again. The man is impressed at how quickly she seems to have bonded with the baby they accepted from the arms of a teenage mother—whose name they were not allowed to know—only three weeks ago.

The third man rocks the baby the way they were taught at adoption classes. Softly, softly, back and forth. The baby’s eyes flutter open and the man smiles down at his son, his first child, his baby. “Who’s a good boy?” he sings, hoping that a bond will grow between them too. “Who? Who?”

The baby does not smile, but do babies this young even smile? The third man now feels silly because of what seems like a stern look from the infant, as if the voice he has put on is simply ridiculous, beneath him. How does one feel embarrassed in the sight of a three-week-old baby? He frowns at his child, noticing for the first time some flecks of gray in his irises. He blinks, startled, but the gray is gone. A wink, a flash, a warning.

“You’re not a good boy,” the man whispers, queasy, no longer singing, no longer rocking. “Are you?”

![]()

There was another boy, once. But that was so long ago.

From Ghostroots: Stories. Copyright © 2024 by ’Pemi Aguda. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.