In our sixth annual look at the debut authors of some of the year’s most inquisitive, innovative, and impactful essay collections, memoirs, and other books of literary nonfiction, Eirinie Carson writes about her memoir of life after the sudden loss of a close friend, Leah Myers details her exploration of four generations of women in the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe of the Pacific Northwest, Andrew Leland describes the personal narrative and historical and cultural investigations that went into his book on his gradual transition from full vision to blindness, Jen Soriano poses the questions she needed to answer in order to complete her essay collection about the impacts of transgenerational trauma, and Jami Nakamura Lin explains the writing process that led to her genre-bending memoir of how we learn to live with the things that haunt us. “The New Nonfiction 2023” takes us on five unique journeys through the writing and publication of a first book of nonfiction, five stories of writing that required different approaches, perspectives—and timelines. But as Soriano says, “There is no early or late for book debuts—there is only right on time.”

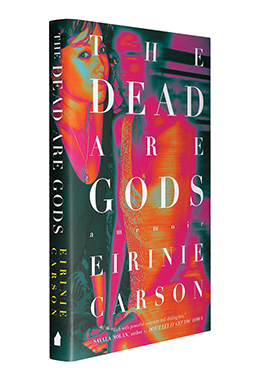

The Dead Are Gods (Melville House, April) by Eirinie Carson

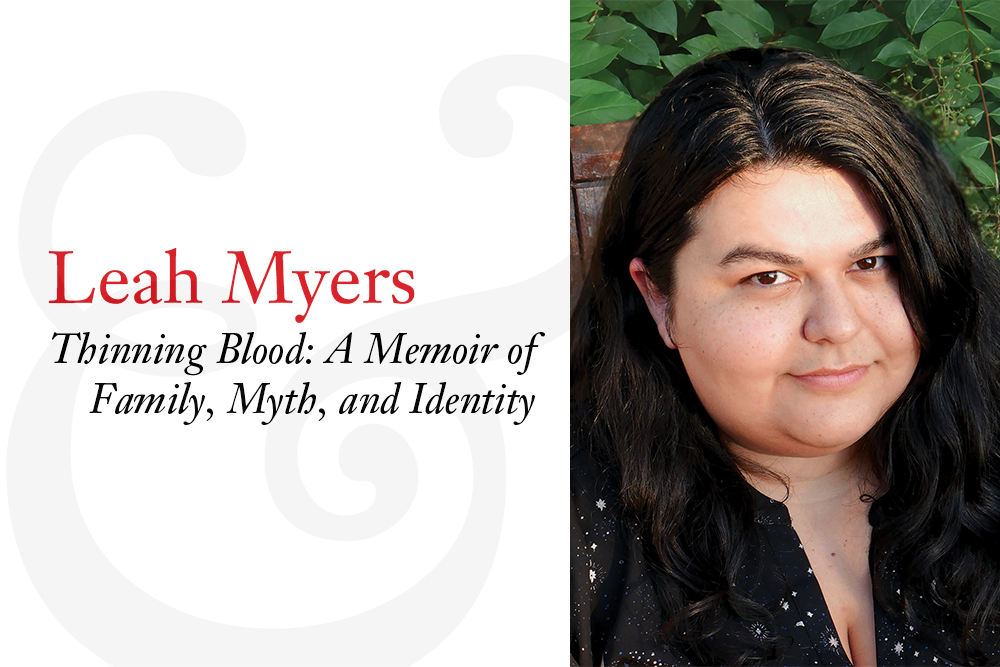

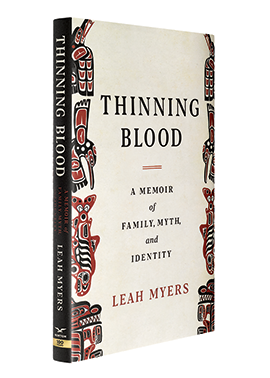

Thinning Blood: A Memoir of Family, Myth, and Identity (Norton, May) by Leah Myers

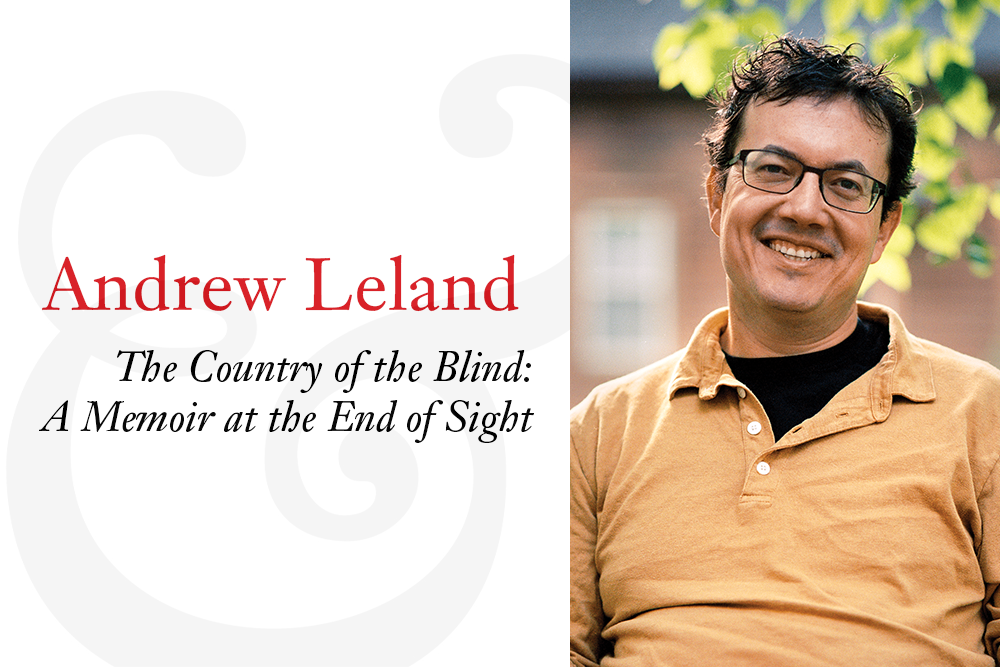

The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the End of Sight (Penguin Press, July) by Andrew Leland

Nervous: Essays on Heritage and Healing (Amistad, August) by Jen Soriano

The Night Parade: A Speculative Memoir (Mariner Books, October) by Jami Nakamura Lin

[1]

The Dead Are Gods (Melville House, April), a debut memoir about life after the sudden loss of a close friend that plumbs the depths of grief, pulls memories filled with love and joy from the grasp of pain, and explores how those people we are closest to help forge our identity and sense of self. Agent: Tim Wojcik of Levine Greenberg Rostan Literary Agency. Editor: Athena Bryan. First Lines: “My best friend, Larissa, died three years ago. A sudden death, improbable and unexpected. She died a week after my thirty-first birthday, two weeks after her thirty-second. A vibrant human, also improbable and unexpected: a cool rock-and-roll type with a love of poetry. An enigma, hard to gain a grip on, a mythical woman, indulgent, reverent. Loved by us all.” (Credit: Kirby Stenger)

![]()

The Dead Are Gods began as a eulogy for my best friend, Larissa, whose sudden death in 2018 left me reeling. I was a caricature of grief in the wake of her death, clutching my heart, gasping, my face perpetually damp and salty. I began with the eulogy for her funeral, fragments of which appear in the book itself, and then I found I couldn’t stop writing. It poured out of me. At first it was merely to gather all those shared memories that seemed to be slipping through my fingers, things that at first felt dumb to hold on to because who would care? Who would take the gift of our stories and treasure them? But then this nostalgia turned to reflection, as it often does, and my writing became the main source of my grief processing. My friend and occasional writing partner read my essays, my musings, and suggested that I had a book on my hands. After some hesitancy—because I am not a trained writer and hold no MFA, and impostor syndrome is a bitch—I tried to focus on making my work into a story, with an arc, with lessons, with meaning beyond just Larissa and me.

I didn’t want to leave the reader with the feeling that I was a preacher in a pulpit, reducing Larissa to some long-dead god, frozen perfect and pristine. After she died I would pore over old voice notes she left me on our WhatsApp chats, replaying her laugh over and over. I wanted to get some of that magic, some of the real Larissa on the page, but audio is hard to write, so I added e-mails and texts from our decades-long friendship to break up the chapters. In them you can read our silly pet names for each other, our trepidation about our modeling careers, the names of the bands and the celebrities we revered as teens and young adults, our willingness to use the last of our rent money to go get a glass of wine together somewhere fancy. I did my best to conjure up Larissa, and of course there are parts of her that are intangible, but I think readers are able to meet her, my best friend, eternal and flawed, in the pages of this book.

My first reach for an agent went to Danielle Svetcov of Levine Greenberg Rostan, who put me in touch with my now agent, Tim Wojcik. He was enthusiastic and touched by my work, which was almost complete. We spent a year together polishing it up, mid-pandemic, before sending it out on submission. The submission part was hard; the impostor syndrome caused me to assume every rejection was because I was a lifelong model and not a college graduate. Finally, we met Athena Bryan, who was then a Melville House editor, and thank God we did because at Melville House I found a team willing to not only field all my very green questions, but to push me and my book into realms I had never thought possible. The Dead Are Gods received a starred review from Kirkus and has been featured by Oprah Daily, Good Morning America, Nylon, People, and the Washington Post, to name a few, and still when I see it in bookstores I let out a little squeal because Look, Larry! Look what we did! In writing this book I fell more in love with my best friend. I discovered things about her and myself and society’s relationship to grieving that may never have come to light in other circumstances, and in doing so I reached a hand out into the ether and it was grasped by a community of grieving people. And of course of course of course of course I would give all of that back to have one more moment with my girl, to stand and have her nestle in my neck as we hug, to take my hand in her long, thin fingers, to have her say, one last time, “Do you want to go get a glass of wine?”

Of course.