For our twenty-third annual roundup of the summer’s best debut fiction, we asked five writers to introduce this year’s group of debut authors, and in the process they not only offered a reading list of five books that mark the arrival of exciting authors whose work readers will be enjoying for a long, long time but also uncovered truths about the art of fiction and the different ways writers draw on the people, places, ideas, and things they encounter in their own lives to build new worlds and tell new stories.

Maisy Card talks with Tyriek White about his novel, We Are a Haunting. “One of the biggest things I wanted to do was just write a story about my community, about my neighborhood, and capture the anxiety of growing up but also the wonder of growing up in a place,” says White. Kim Fu interviews Ada Zhang, author of the story collection The Sorrows of Others: “These stories feature lonely characters, and it comforts me—makes me feel less lonely—to think of them together.” V. V. Ganeshananthan talks with Mihret Sibhat about her novel, The History of a Difficult Child: “In my novel, humor is the primary ingredient that raised the tragic raw materials of my childhood to a level of art,” says Sibhat. “By giving me a chance to approach grief from an oblique angle, humor helped me see old stories anew.” Naheed Phiroze Patel and Shasri Akella discuss Akella’s novel, The Sea Elephants: “I worked with a street theater troupe in India for three months, traveling with them, writing the stories they performed. I often relocated myths to the present day to accommodate current issues or retold them from the perspective of a minor character.” And Tiffany Tsao introduces Rebekah Bergman, author of the novel The Museum of Human History: “I do think writing this novel changed me,” Bergman says. “It certainly changed how I think of my identity as a writer.”

We Are a Haunting (Astra, April) by Tyriek White

The Sorrows of Others (A Public Space, May) by Ada Zhang

The History of a Difficult Child (Viking, June) by Mihret Sibhat

The Sea Elephants (Flatiron, July) by Shastri Akella

The Museum of Human History (Tin House, August) by Rebekah Bergman

tyriekwhitemaisycard.png

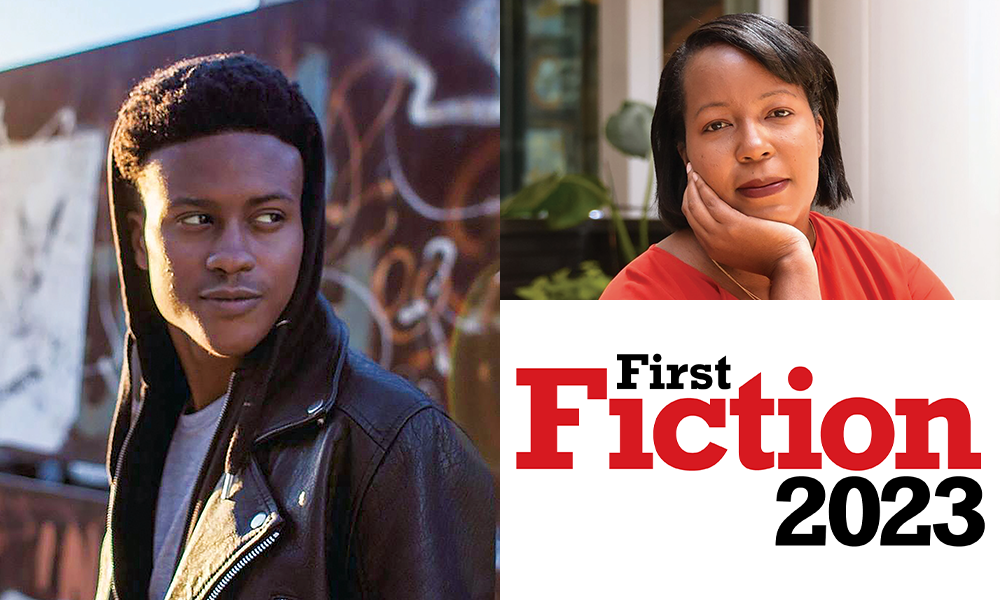

Tyriek White, whose debut novel, We Are a Haunting, was published by Astra House in April, introduced by Maisy Card, author of the novel These Ghosts Are Family, published by Simon and Schuster in 2020. (Credit: White: Zoraya Lua; Card: Tehsuan Glover)

![]()

Tyriek White’s debut novel, We Are a Haunting, strikes me as both a love letter to New York City and a kind of elegy. The novel alternates between the stories of Key, a doula who can see and communicate with the dead, and her son, Colly, who lives alone in the family’s apartment in the East New York neighborhood of Brooklyn, raising himself after Key dies from cancer. Colly inherits his mother’s and grandmother’s connection to the spiritual world, which allows Key to remain a presence in his life, guiding him even after her death. Together they tell the story of their community and how they and their neighbors navigate decades of crumbling public housing infrastructure, violence, and poverty.

The writing, on both a sentence and a structural level, is magical. As I read I felt increasingly unanchored in time. I had flashbacks of the beautiful parts of growing up in New York City, but I was also flooded with visceral memories of what it was like to be part of a working-class family in the 1990s—our struggle to hold our place in a city that has grown increasingly hostile to the poor. But the ghosts in the novel do not let us despair. While they remind us that Colly’s neighborhood falls on a continuum of Black disenfranchisement in the Americas, the ghosts also illuminate the cultural and spiritual practices that enslaved Africans and their descendants have drawn from and created to retain a sense of community, no matter how many times we’ve been forced to begin anew.

Kiese Laymon describes your book as “so New York—yet so deeply Southern on lower frequencies.” I know you received your MFA from the University of Mississippi. Did you go down south as a child, or was this your first time living in the South? What effect did it have on your writing process?

My family is from North Carolina, so I’ve been down south. I’ve loved going down for the summers, but Mississippi was definitely a bit of a shock, for a combination of reasons. I discovered a vibrant radical community there but was also negotiating that with the political realities of the place. I think it unlocked how I wanted to talk about this world. I’ve been in New York for so long that changing my relationship with space or geography, moving all the way down south kind of upended how I wanted to write about this urban environment. I used a lot of natural language. I think the sensibilities are probably very Southern.

Considering that you were writing from a distance, what resources did you draw from to render New York City so vividly?

In literary terms the novel is very much in that lineage of Jazz by Toni Morrison or The Fortress of Solitude by Jonathan Lethem. I was taking those imaginings of New York and sort of inserting myself. One of the biggest things I wanted to do was just write a story about my community, about my neighborhood, and capture the anxiety of growing up but also the wonder of growing up in a place. Being from the outer boroughs, being on these outskirts, and seeing how that informs our understanding of empire and power, I wanted to write about people who love and care for each other and also how we push forward in communities like ours. I think that was my main goal but also that haunting sense of the past. The way we navigate our streets, the street names being from slave owners or politicians of eras past. How does that affect the weight of your footsteps, in a sense, walking through your neighborhood or your community?

A lot of the landscapes that you described felt intimately familiar to you, but I was curious about the research you did for the book. The supernatural element connects the past with the present. There’s a moment when Key is talking to the ghost of a slave in an abandoned part of Brooklyn, and I assumed that you were describing a place that still exists. Were there spaces in the city that you weren’t familiar with that you explored for the novel?

For sure. There’s an old Brooklyn Eagle article that I drew heavily from. There’s this Dutch reformed-style church a block or two down from where I grew up. The article, from the late 1800s, describes how white folk were interred or buried in the back of the church, but also how they had this space or section where Black people were buried—in a little corner of this cemetery behind the church. And then, if not, they were buried across the road or something. I was compelled by that image of Black folk during that time. There were free men, like in the Weeksville community, but a lot of them were also enslaved, and so what were their burial practices or ceremonial practices at this point when they didn’t have a place to bury their own? I was so intrigued by the idea of sort of figuring out or finding that space. A lot of those scenes reverberate with that.

Your bio mentions that you’re a musician. Were you a musician or a writer first? Can you speak to how music informed your writing process?

I’d say I was a writer first, but I’ve been into music since I was eleven or twelve, when I was writing lyrics in middle school. I have a machine sampler, some keyboards, a separate place for my brain to tinker around other than the page. They tell you being a writer is an isolated practice, but I don’t believe it has to be. In contrast, music is just extremely collaborative. So I think about what principles, what practices I can sort of absorb and take back to the page.

The musical references in the book stood out to me. It felt like each character had their own soundtrack, and music was also used to signal the shift or passage of time.

Right. It’s used to organize time and where each character is. There’s a soundtrack for the book; there’s also a soundtrack that I used to write the book. And not just a whole playlist, but the beats that I wrote this book to. I think that’s a big part of the process. Other art is in the background, too, but mostly music.

An excerpt from We Are a Haunting

One day, I fell backward into a scar in the world, a fall sudden and lasting. A portal took me whole, sent me traveling across a pulse that could split me down the middle. I tumbled out the other side, a terrible moaning like a hive of meat bees. I had been pedaling down the block on an unkempt length of road on Flatlands, barreling ahead, ripping along twisted storefronts and storage lots. The smell of hot metal filled the air, lodged itself at the back of my tongue and burned as I tried to catch my breath. I had reached the Belt Parkway and the creek widened, blooming into the bay and into the Atlantic, the dark basin, murky with trash and wildlife, boats twinkling in the distance. The water emptied into a reservoir where it was drained and then treated. There were heating and waste stations, chimneys that gagged out heavy smoke and stray embers into the clouds over the land. A bridge reached over the harbor, kept Far Rockaway at bay, the lights from ferries and small boats parting thedarkness. In the distance, I saw the shape of Boulevard through the fog, apartments stacked atop one another, our city in the clouds, embassies of time, crashing dimensions and histories, the cursed, the lost, the all-seeing. No different from Ingersoll Houses, or Marcus Garvey, or Tilden; Chelsea, or Pink Houses, or Brevoort; Farragut, or Walt Whitman Houses, or Baisley Park. No different from Saint Nicholas, or Queensbridge, or Mott Haven.

You died without telling me what it was like to be in two places, without designation, without home, no matter how hard you try to make one for yourself.

When I reach out for you, tipping over, into a slippage of time. I feel my body grow open, my hand wrapped in another. This is Nana, blood rushing to her fingers, her hands the color of pink salt. We are in the doorjamb of a temporary house. I see a shoal of folk near the center of a settlement farther down, along the gray water. I follow the sound. A dirt path like a welt stretching toward the sea. I slip through the cattails and the buttonbushes, under the river birches and needles of the bald cypress. The smell stays with me, on my hands and in my hair. The smoke above the huts on the beach carried spiced meats and greens. Through the bramble, the band of sweet pepperbush, I see the shore open up, the ocean flat. Cloudy. The person standing in front of me didn’t look like anyone I knew but felt like you. A ways down the beach I heard a crowd; the smell of fresh meats and spices from an open market. High tide sounds like a stampede. My feet are sinking into the loam, the wet paste of sand and dirt. I am barefoot in the duckweed. You see me, the same expression in my dreams, a sad smile.

“Oh, baby, when did it hurt so bad?” you ask. Not why does it hurt, or where does it hurt, but when? I feel like all the times, the time before me, an ache that was precolonial, a Paleolithic expanse of sorrow. You are Cybele carved in Anatolian stone.

“You were just gone one morning,” I tell you. “And I know it sounds like I blame you but I don’t.”

“Yes, you do.”

“That’s not fair.”

“Are love and sacrifice not dark synonyms for one another?”

I turn away, take a few steps up the beach. When all felt lost, being seen through your grief, really seen, was all that mattered. What if, I always thought, if I never met you, never felt you gone because you weren’t there in the first place. In my mind, it was like being without something from birth— sight or a limb—and how it compared to having the thing, losing it, then living the rest of a life without it. Inevitably, the thing dries and crumbles like sand and one is forced to dream away the incessant drum of missing, make themselves anew. When you died, Pop told me I’d only think of life in two phases: life with you and life without you. Said when he lost his own mother, folk could only see him as an unfinished body, what was sundered, removed. Never how he created a new whole, had to reimagine what those parts left could amount to. After he’d finished his stories, I would try to drift to sleep without thinking about the old him, the sawed-through flesh and muscle, the hacking of bone, the dark blood that painted the emergency room. I tried to imagine anything else besides the yellows and browns his body leaked, the pus, the clotting of fluid, a cursive written on his skin and across smocks and sinking through sheets. If I never knew you, perhaps I’d still be who I was before you died. I would never do the hard work of looking beyond myself to see others suffering along with me, that the world and the human condition were threaded around the work of community, our care for one another. I feel my gut stir when I look back at you—remorse. I want you to know the new ways I could love, which I had learned for better or for worse.

“Here,” you say, easing me into the current. A cool wind from the ocean had pelted sand into my hair. It stung my eyes, made me shiver down to my toes. There was a hole in the night sky, where it all goes in the end, some giant we’ve mistaken for sun or light. I have this strange feeling of culmination, what could be made of all those histories, an infinite process—hilltop city of seven waters. “I’ll tell you everything.”

Excerpted from We Are a Haunting by Tyriek White. Published by Astra House. Copyright © Tyriek White 2023. All rights reserved.