For our twenty-second annual roundup of the summer’s best debut fiction, we asked five writers to introduce this year’s group of debut authors, and in the process they uncovered provocative truths not only about these specific books and their talented authors, but also about the art of fiction and the ways in which writers engage the people, places, things, and ideas around them as they mix the unpredictable and extraordinary alchemy of world-building with truth-telling.

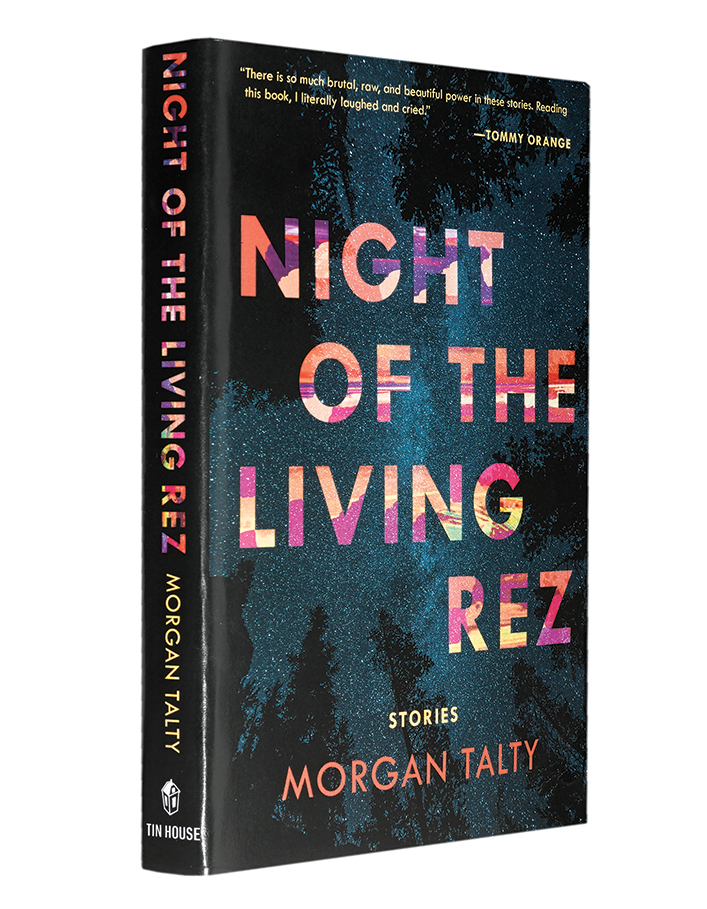

Kiese Laymon talks with Leila Mottley about her novel, Nightcrawling. “I wanted to find a way to communicate the complexities of home and the dualities of loving something that is both a constant and a thing always changing,” says Mottley. Tsering Wangmo Dhompa interviews Tsering Yangzom Lama, author of the novel We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies: “With this novel I wanted to focus on the lives of ordinary Tibetans, far from the centers of power.” Jamel Brinkley talks with Arinze Ifeakandu about his story collection, God’s Children Are Little Broken Things: “The stories are tied together for me by the idea of home, as person, place, or thing, and by the fact that the characters are always looking, searching for, and often choosing home,” says Ifeakandu. YZ Chin and Paige Clark discuss Clark’s story collection, She Is Haunted: “Life and stories about life resist neat packaging; it is perhaps this push to resolve unresolvable feelings and situations that leads to characters acting out in unexpected ways.” And Brandon Hobson introduces Morgan Talty, author of the story collection Night of the Living Rez: “It means a great deal to me to be part of this new generation of Indigenous writers,” Talty says. “We’re all contributing work that I believe is really pushing against the archetypal images and hackneyed tropes out there about Native peoples, particularly in popular culture.”

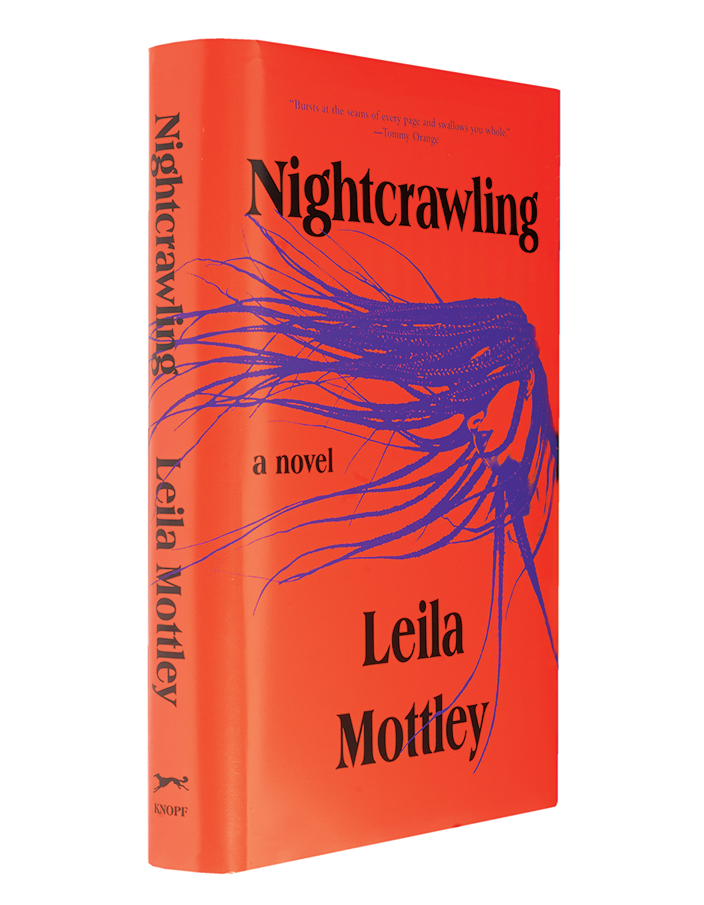

Nightcrawling (Knopf, June) by Leila Mottley

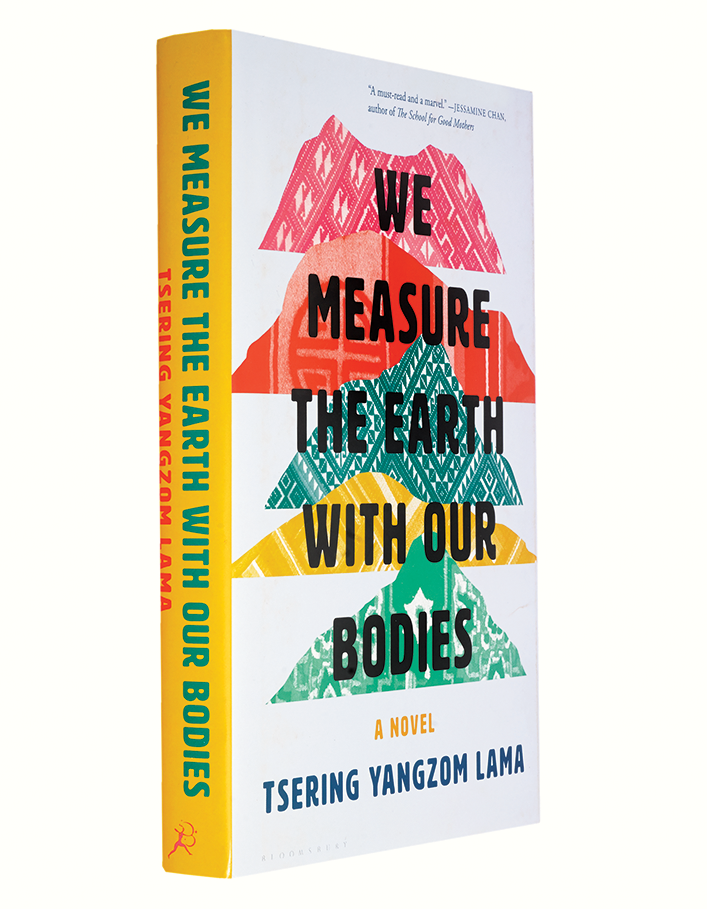

We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies (Bloomsbury, May) by Tsering Yangzom Lama

God’s Children Are Little Broken Things (A Public Space Books, June) by Arinze Ifeakandu

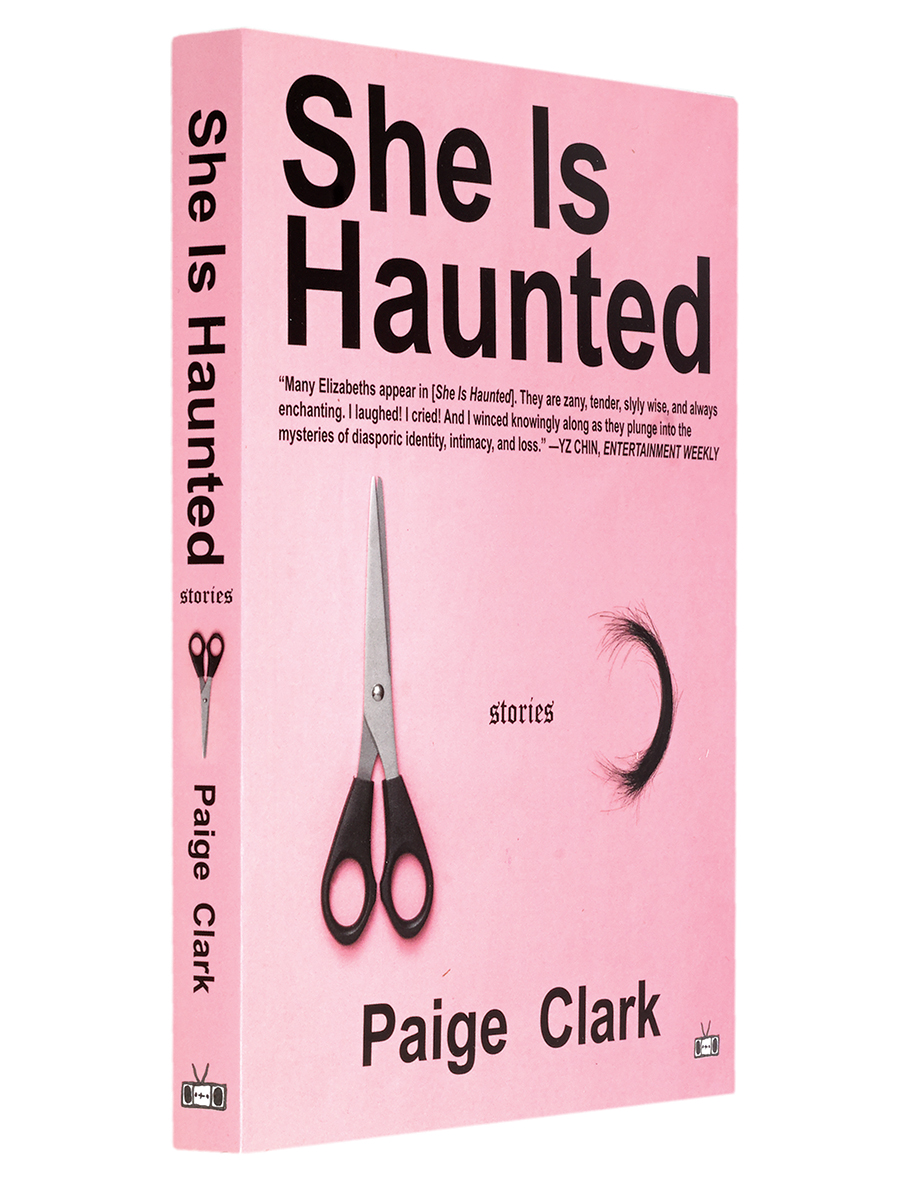

She Is Haunted (Two Dollar Radio, May) by Paige Clark

Night of the Living Rez (Tin House, July) by Morgan Talty

leila.jpg

Leila Mottley, whose debut novel, Nightcrawling, was published in June by Knopf, introduced by Kiese Laymon, author of three books, most recently Heavy: An American Memoir, published by Scribner in 2018. (Credit: Mottley: Magdalena Frigo)

![]()

I am leaving northern Mississippi, likely forever, the night I read Justice Alito’s draft opinion that would obliterate healthy reproductive choice for millions of specifically poor young Black women.

And I’m thinking about Leila Mottley’s Nightcrawling.

There is a excellent argument to be made that Nightcrawling is the most compelling book written by an American teenager in my lifetime. Somehow, even that feels too brittle, too boring, for the way Leila Mottley, nineteen, pulls us through a body, a city, and a nation equally consumed with crawling toward liberation and jogging toward inequitable failure for our narrator, Kiara, or Kia. Nightcrawling is a scorching, layered, incredibly readable book that takes seriously the task of readerly provocation on every page. We needed it before the Alito leak, and honestly, we need it more—much, much more—after. Get ready. Or don’t. It doesn’t matter. Leila Mottley is here. And she is doing her part to reckon with what Treva Lindsey calls living through “unlivability.” This is our conversation.

Nightcrawling blew my mind and my heart. More than anything it made me want to write. How has the dream of writing an incredible book differed from the act of writing an incredible book?

I’ve always been a reader, and I read with an eye toward craft, and I think that has created really high expectations for what a book can be. So before I started writing Nightcrawling, I had an image in my head of the completed work and how it could be everything I’d want to see as a reader. I also had an image of what it would be like to write, which in my head was many wistful days at cafés and ease and endless excitement. I think fantasy is an integral part of the writing process, and without my overdeveloped imagination curating an image of writing and literature, I don’t think I’d have been able to make it through the tedious, messy, challenging parts of writing. The reality of the writing process requires a lot of dedication to the work even when it feels like it doesn’t match the vision. After I wrote the first draft of Nightcrawling, I read it back, and while there were parts that I loved, it didn’t live up to what it was in my head. I have since realized that it’s not supposed to, and as much as I love the drafting process, I feel a sense of relief knowing that no matter what my writing looks like after that first draft, it doesn’t have to stay that way.

Are there specific readers you want to love Nightcrawling, and can you talk a bit about how the idea of home worked into the construction of the book? I was obsessed with the pacing of the book and wonder what imagined reader was pulling you through the crafting.

When I’m writing the first draft, I try to think of the reader as little as possible because even the idea of perception can interfere with getting the most honest story on the page, so in some ways I am writing only for myself. It’s sort of a cliché, but I wrote Nightcrawling because it was the book I needed to read when I was seventeen. In revision I start to think about the reader as whoever my narrator would be most likely to tell their story to. For Kiara I tried to center Black teenagers because I think she would want to be most understood by those she identifies with. Gender and its dynamics in Black spaces and among young people had a large influence on the book too. I wanted Nightcrawling to be a window into the mind and life of teenage Black girls, both so that we can feel more visible and integrated into mainstream narratives and so that others can begin to see us as vulnerable people. It was important to me to acknowledge Black teenage boys as potential readers too and hold compassion for the ways in which they are often given a very narrow definition of success that asks them to participate in the dismissal and demeaning of Black girls and women.

As for home, I felt strongly I needed the book to be based in Oakland, since it’s where I was born and raised and it’s the focal point of my entire world. I wanted to give voice to my experiences in a city that is depicted as simultaneously dangerous and desirable, neither of which leaves much space for the love and unique belonging I feel in Oakland or how this city has harmed its own people. I wanted to find a way to communicate the complexity of home and the dualities of loving something that is both a constant and a thing always changing.

You talk about “gender and its dynamics in Black spaces and among young people.” When I read Nightcrawling, I did that dual thing we do as writer-readers where I was absolutely blown away but also worried that folks would fetishize your age.

Yes, people fetishizing my age was actually a major anxiety for me, and I’m still struggling with how to hold my discomfort with the attention I get for my age and my hope that, even if that’s what brings people to this book, they take something away from it that has nothing to do with me. I’m not the first or last Black kid to be praised as exceptional, and I always try to put it into the perspective that when people applaud me for doing something because I am young, they are also indirectly saying that they expect very little of young people and that the thing that makes me special is what I have done and not who I am. The pressure to overachieve for Black kids goes beyond what our parents or teachers want for us or even what we want for ourselves, as I think many of us feel like the only way we will be seen, respected, or loved is if we do something that no adult would expect out of us, expectations which can go from forming a coherent sentence to writing a book or signing a record deal or being drafted for a professional sports team. I’ve spent a lot of my life conforming to this pressure, and I’ve become accustomed to it, but it’s still uncomfortable and sometimes disparaging to have the first thing people tell me be that they cannot believe that I wrote this book at seventeen. I knew the moment I stepped into the world with this book that this was going to be a reality, and I truly hope that this book can have an impact on readers profound enough that my age becomes the least important thing about it.

What do you hope that young Black folks in Oakland do with the world you’ve created in Nightcrawling?

Novels about Black people in U.S. cities are often pegged as “urban fiction,” which is elitist code for “poor fiction,” which I guess is supposed to imply that this kind of art isn’t worthy of close reading or respect. I think the depiction of city novels centering Black characters and the genre redlining that goes with it ends up communicating to us that Black people in cities don’t matter or are simply there for speculation or entertainment to be classified away from “literature.” But there is more to every Black city and neighborhood than most of this country even bothers to consider, and the categories created by the publishing world fail to recognize that Black people like to read complex books and also want to see those complex books set in our worlds. Across the board we don’t have very many representations of Oakland in literature. We have There There by Tommy Orange, which I love, but he writes about a different Oakland than the one in Nightcrawling. Most other depictions of Oakland, particularly in the media, are either the gentrified white version of Oakland that the travel articles say is now worth considering for a visit, or the “bad” parts of Oakland they say you should never go to if you don’t want to get mugged. But if you grew up in East or West Oakland, you never even begin to think about yourself or your neighborhood or your city in this binary. Our worlds are rich and complex and full of so much more than might meet the eye of an outsider, but we see it all, and I intended this book to mirror that back. So I hope that young Black people in Oakland feel affirmed by Nightcrawling and are able to hold a spectrum of feelings about our world and, ultimately, remember that we deserve to have control over the narrative of our city.

Kia made me really reconsider the unspoken, insidious ways so many people who make up our systems and institutions crave the exploitation of Black girls. And Kia is so much more than her exploitation. Can you talk a bit about the importance of emotional flexibility and interiority in Kia’s character, particularly when she’s at her most vulnerable?

I think a lot of people assume that Black people and Black teenagers specifically don’t have vibrant and complicated interior lives, which is so far from true. Part of the reason I chose to write Nightcrawling through Kiara’s first-person point of view is because I wanted people to be able to see into Kia’s head, where she is trying to make sense of a world that abuses and denigrates her. Particularly in the moments when Kia is in a position where she knows she has no escape, I wanted to show how we find ways to survive these experiences and how that relies on an adaptability and oscillation between detachment and resistance. When a body is being rendered as an object to be used, we need to find a way to experience ourselves outside of that physical moment, so Kiara finds herself poeticizing or personifying her body as something separate from her. It was definitely a challenge for me to not find myself fully intertwined with Kiara because I was essentially living in her head while I wrote Nightcrawling, and while her head is an intricate and vivid place, it was also overwhelming at times to move between the many internal methods Kiara uses to survive.

And my next question is really about the paradox of the narrative of Nightcrawling and the physical book, Nightcrawling. I learned so much about critiquing our complicity in capitalism from activists and artists in Oakland, and your book is a staggering critique of gender, race, labor, and sanctioned exploitation. What do you make of the paradox of a story as brilliantly constructed and politically potent as yours being sold as a product? The first time I saw my book in Walmart, I smiled. Then I cried. What do we do with this paradox?

God, this is such a good question, and I also find myself struggling to contend with it. My systems of belief don’t always align with the constraints of the capitalist structures that force us to rely on them in order to survive. On one hand a book is a product of labor, and I believe that within the country we currently live in, compensation for labor is necessary. On the other hand Amazon and other large corporations account for such a huge percentage of book sales, which in turn contributes to the continuation of a system of exploitation. I’ve also learned most of what I know about the ways we navigate capitalism from the Oakland activist tradition. And one of the guiding principles that has stuck with me is rejecting the idea that, as Black people asserting our power, we must fight capitalism with Black capitalism. So it doesn’t make me feel better to have my book, one that critiques the self-seeking logic of capitalist pursuits, being sold in these corporate institutions. Because I know no matter what percentage of profit goes to those of us who played a part in making or selling this book, a huge fraction is going back into a system I claim to not support. I don’t know what we do with this paradox, but I know that the Black socialist leaders I have learned from stand by an understanding that you cannot rebel against a system without sacrificing something. It’s an incredibly difficult thing to do when we are socialized in a culture that values individualism and the protection of oneself over all else, especially as an artist facing the pressure to find ways to survive in this economic system. So I believe that at some point we will need to decide that the principle of breaking free from capitalism and all that comes with it is more important than our individual gains.

I want this last answer to be the wallpaper of my office. What’s a perfect hour for you right now in your life, Leila?

My perfect hour right now is lying in the sun in the park with my notebook and my partner reading beside me. Surrounded by a kind of stillness that isn’t silent but just complete joyous peace, with all these kids running around playing basketball and eating grass and me just getting to witness it as I write whatever I want to write without any pressure or expectations.

An excerpt from Nightcrawling

The sound of splashing wakes me up at noon. It’s foreign to me here, the water thrash noises both recognizable and out of place. Something’s always waking me up in the height of my happy, right when my dream begins to dance. During last night’s sleep, which really didn’t start till four a.m., I dreamed up this meadow with flowers that exist in colors I’ve never seen in person. I could hear this melodic soundtrack, this Van Morrison kind of blues, and I couldn’t figure out where it was coming from until I lay down in the flowers and realized it was coming straight from the sky. And then I was laughing because the sky was singing to me. God walked out the clouds like music. I was naked. I am always naked. And then there was a splash, bright midday through the shades, this empty apartment.

I stumble up from the mattress, swinging open the door and hanging my torso off the railing, so my body splits in two at the stomach: legs and breasts. Crust crumbles out my eyelids as I stare down into the pool, the scene materializing like a television turning from static to moving image. Trevor’s head bobs up and down, in and out of the water. He’s tall enough now to stand in the shallow end, but continues to dip his head under, moving it around; circles of boy turned fish.

“What you doing in there, boy? There’s shit in that water,” I call down to him. Though the brown of it has disappeared, probably through the filter, I swear I can still smell the feces lingering in the air. As far as I’m concerned, Dee’s man’s dog shit and the pool are interchangeable.

Trevor’s head comes up, bends back to look at me. He has a birth-mark on the top of his head, a dark spot in the shape of a spilling circle and I can see it as clearly now as I could the day he came out his mama. The whole apartment building went into labor with Dee when her moans found their way through the vents and out the windows. We all sweated with her, paced around and counted the minutes between each choke of her body. Mama was looking at the clock in our apartment, waiting for a couple hours until she turned to me and said, “It’s time. Come on, chile,” and just like that we were out the door and knocking on Dee’s apartment, in a flock of women all joining the stampede of this birth, my eight-year-old shoulders shaking. Every woman in the Regal- Hi crammed into Dee’s studio apartment, where she was splayed on the floor, gaping like the pocket of sky before the rain starts to pound, ready to bust open and release itself.

Dee kept saying, “Give it to me, please, just to get me through, Ronda.”

She repeated this like a mantra between contractions, referring to the rock and pipe on the kitchen counter, ready for her. She said she had quit her habit after she found out about the pregnancy, but by quit she meant she used only on occasion, only when the morning sickness or the back cramping got real bad. Ronda, her childhood friend, refused to give Dee the crack, and a group of women stood in a line between the counter and Dee’s body, guarding the child from its mother.

Mama pushed her way through the crowd, her arms long and spread out, me trailing behind her toward the center of the room, toward Dee’s pounding.

“We got a little longer till he’s out, alright, baby? It’ll be over in about one hour. One more hour, one more hour.” Mama repeated this, dropping to the floor by Dee and humming until the whole room was one rumble of my mama’s lungs, intoxicating and heavenly, and I couldn’t help but want to climb back into her body, feel those vibrations like my own breath.

Dee wailed and squeezed and trembled until my mama’s hums drowned it all out and then the tribe of us saw the hair, saw the tiny round that crawled from her body, turning her inside out. The squeals began and the humming turned to chants and we all watched that child swim out his mama, head poking out more blood than hair, and my mama took him into her arms and laid him on Dee’s breast and this was the sweetest, most whole thing to ever take place in our building, and the rain poured and poured and poured until Dee began to beg again and her birthmarked baby squirmed and Ronda gave up, passed Dee the pipe, and she faded into sky like she didn’t hear her own baby crying. And Trevor cried and she smiled and we all hummed again.

![]()

Trevor splashes down below, looking up at me.

“Lost my ball,” he calls.

“What you talkin’ about? Why you not at school?”

“Mama not here and I woke up late and then I was gonna go but I dropped my keychain in the pool and if I don’t got it, then the boys don’t win the game and I lose my money.”

I ask him, “What money?” but he simply dips back down into the water until the only thing distinctly him is that circular mark on his head, roaming. His pile of clothes is now wet from the splashing and when he emerges, small metal basketball keychain in hand, his boxers are slipping off him. I see the outline of his ribs like they been carved out of him and the rest of my day fades like a dream. I walk toward the stairwell down to the pool and Trevor starts climbing up, pile of clothes a lump in his arms. We meet at the halfway point of the stairwell, Trevor a head shorter than me at age nine, with arms and legs that seem to stretch farther than he can control, but his face is still childlike.

“Go on and put some new clothes on,” I tell him, beginning to guide him up the stairs.

“We goin’ somewhere?” Trevor’s teeth flash, always eager for the escape.

I grab the keychain out of his hand and look at it, taking in the way it shines like somebody been scrubbing it clean and tucking it into bed every night. “You wanna play ball so bad, let’s go on and do it.”

At that, little boy limbs fly straight up the stairs and into the apartment, just like they always have. His legs are longer and he knows more about what kind of life he has than he did when he was three and racing around the building, knocking on everyone’s door, but he is still the same buoyant little man.

Dee tried to be his mother for the first few years of Trevor’s life, at least enough that she was home half the time and she bought formula and bothered to make sure somebody was watching him when she went off to go get high in some other apartment. She used to leave Trevor with one of the women, sometimes Mama, any of the aunties who inherited all the Regal-Hi’s children once theirs grew up. Then, between Daddy’s death and Mama’s arrest, all the aunties left. It was like something had come over the building and they all scattered, women disintegrating into nothing. Some chose to go and some got evicted, some passed away and some remarried, but all the women who had helped raise Marcus and me were gone by the time Trevor turned seven and then it was just us, motherless.

Trevor started to come around more often after that and then I was walking him to the bus, finding him some extra Doritos for after school. I was determined not to let nobody toss him away. So when the rent notice got posted, when Polka Dot came up to me and showed me what my body was worth, I thought maybe this was a ticket out for the both of us. Maybe this was how we got free.

I head back into my apartment and Marcus is awake, rubbing his eyes on the couch.

“Mornin’,” he says.

I sit down next to him, thinking about how it felt to be in the second man’s car last night, about Tony’s back as he walked away. It was different when I was alone, the fear escalating and the grit so profound that when I got home last night I showered longer than I ever have before, didn’t even worry about the water bill. I don’t know if I can do it again, but I also don’t know how to keep us alive if I don’t. “Marcus, I gotta ask you something.”

He looks at me, rests his cheek in his hand, waits.

“I know I said I’d give you a month to work on the album, but I need you to get a job.”

Marcus starts to nod slowly, looking at the carpet and then back up at me.

“Aight, Ki. I’ll start looking.”

I didn’t expect him to say yes, so when he does, it’s like there’s suddenly more air in the room, his nod a solace that might make up for everything.

“I actually got a lead for you. I ran into Lacy a few days ago. She works at a strip club downtown and I bet she’d help you get a job there if you asked.”

“You know Lacy and I ain’t tight like that no more.”

“You know you ain’t gonna be able to get no other job.” I pick at a scab forming on my knee. “Please.”

Marcus nods again and I lean forward, wrap my arms around him like I’ve been wanting to since Polka Dot. He kisses the top of my head, murmurs something about needing to piss, and I think for the first time in months, we might just be okay.

Marcus leaves to go piss at the liquor store and I pull on a jacket and head back to the patio strip where all the apartments connect in a circle around the shit pool. Trevor still hasn’t come out from his door and I decide to just head in anyways, opening the door to a scene of little boy blues, Trevor in his boxers dancing. Swing step, head bob.

The music floats out an old stereo on the floor mattress, half static and half disco song that I’m sure Trevor’s never heard before in his life. And, still, like my dream, he dances. I run into the room, right toward him, and tackle him into a hug that fills with shrieks echoing a sort of happy that is all child before he pushes me away.

“Put them clothes on so we can go.” I breathe heavy, my spine aligned with the stained rug that cushioned our fall. Trevor is blithe, speedy and awake, dressing in seconds. I stand and lead us out the door, into the daylight where it is just Trevor and me under the soft glare of sun.

![]()

For early afternoon when all of us should really be sitting in some kind of classroom, the basketball court is alive with sweat and shuffles. Sneakers move quick enough that the asphalt seems to smoke and my eyes switch from flesh to flesh, everybody merging with sky. Trevor stands next to me with his basketball appearing oversized in front of his bony chest, just watching. Watching the way I watch Alé skateboard: so mesmerized I can’t even begin to move.

We’re standing on the edge of the court when a girl approaches us, basketball shorts clinging to her thighs with midday game sweat. She’s got braids down to her waist, swooped into a ponytail, and she drips with salt, smells like the bay, can’t be more than twelve but she is infinite.

“Never seen you two ’round here,” she spits.

“Must not’ve been looking.” I put my right hand on Trevor’s shoulder so I might be able to tether us together, create a safety net.

Trevor steps forward. “Been betting for months on the morning game. Got a stack of money ’cause of you and your girls.”

I’ve never seen Trevor like this, with a blade for a throat.

She twirls the ball in her hand and Trevor mirrors her with his. The balls are the same size but beside his body, his is massive.

“You been betting on me?” she asks.

“Against you, actually. Don’t got money to waste on nobody who don’t got no game.”

The girl’s salt stench gets thicker in her heat. “You ain’t even know how to hold a ball so you best not go talking like that.”

We all know what a challenge sounds like. We all looking for a fight without fists. This survival. Bay girl seems to expand her body, legs spread, like taking up more of this air might bring her some kind of victory. Trevor tells her the rules of the game, as if he’s ever done more than watch it: two on two, eleven points wins, you foul and you out. Bay girl’s teammate appears by her side like she’s been listening in the whole time: she’s smaller in frame but her arms are thick, coming out from her body and jiggling. Her sweat smells sweet, like jasmine, which probably means she stole her mama’s perfume this morning.

“I ain’t got all day,” I tell them, holding out my hands for Trevor to pass me the ball. It spins right through the air and into my palms.

Jasmine girl tilts her heavy head, squints, and calls out to a boy across the court. The boy is older, maybe fourteen, and I think he might be too skinny for this sport. It’d be too easy to crack a bone, splinter each one of his ribs.

“Sean, come referee this shit.”

Skinny boy saunters over and I look into Trevor’s face, trying to catch a single glimpse of his terror. It’s not there. Instead, there is a determination so fierce it has cemented into a scowl. Sometimes being this young unleashes the fury. I lick my lips, taste my own salt, and I’m ready to swallow the bay, extremities and all.

We separate onto our respective sides of the court, side by side, with Sean in the center. I toss him the ball.

“Y’all better not do some fuck shit. It too early for no fight.” I expected his voice to be higher, but it is a deep pit in his throat, coming out mangled on his tongue.

“We ain’t gonna start nothing,” bay girl spits.

I mirror Trevor’s scowl, nod. “Nah, we playing fair.”

Trevor’s fingers twitch at his sides, legs spread, boy ready to catapult into the game. I don’t remember the last time I played ball, but if Trevor’s gotta win, then I know I best be Steph Curry fourth quarter. I best be everything he ever wanted.

Sean starts the game real quick, throws the ball toward bay girl and she catches it, dips right, then left, then spears her body forward, too fast for Trevor and me to think long enough to stop her. She shoots and the ball swooshes right into the hoop like that’s where it belongs. We stand, stunned, not ready for bay girl to have salt feet to match.

I step toward Trevor, lean into his ear. “It’s all about the way you move. Don’t think about it, just move.”

The next play and Trevor fumbles again, bay girl’s partner catching the ball and running with it. Trevor starts to shake his head and I almost think he’s about to start crying, but when he looks at me, his eyes are fierce.

The ball, back in our possession, is heavier now. I toss it to Trevor, who catches it, bouncing and whirling across the court. Bay girl catches up to him just as he releases the sphere from the three- point line, jumping so high it’s like he’s weightless, the ball springing over our heads before it swooshes straight into the basket.

He comes back down from his jump panting, runs over to me, and we’re both clapping hands and backs, trying to remain collected, but so elated we can barely handle it. Trevor bobs on the tips of his toes just like Alé used to when we were young and out here on this same court, bruising each other with elbows to the ribs and laughing about it later, when we started turning purple. We don’t play no more, but not because we outgrew it or nothing. It’s just that Alé couldn’t stand to look at my skin like that and know her bones caused it to color in a way skin’s not supposed to color. She used to touch the ones on my belly like you might touch a half-dead squirrel and even when I told her to stop that shit, she couldn’t help herself. Sometimes she still looks at me like that.

Back on the court again, watching Trevor bounce side to side, I know the boy is fevered and confident the way winning makes you confident, hands gripping that ball like a godsend. Bay girl learns she likes us even less than she thought and, like a whirl, the game has turned into a beatdown, Trevor and I taking turns dodging their shoves and shooting. The sound of the ball making contact with the hoop is like a deep breath and pretty soon our lungs are full. By the end of the game, we’re both slick with perspiration, hiding smiles as we nod to the girls, and walking off that court. I think Trevor is the most radiant boy I’ve ever laid eyes on: walking home with that ball slipped under his left arm.

It’s almost like I can see the joy droop off him as we approach the gate to the Regal-Hi. The curves in his face dissipate into an angular pout and the only sign that his body was leaping through the air less than ten minutes ago is the sweat still trickling down his cheeks. I squeeze his shoulder as I unlatch the gate and Trevor still doesn’t snap out of it, even when we’re standing by the shit pool and the rest of High Street only exists in sound. I lean down so I’m looking him straight in the eyes. He tilts his head away from my gaze, so I cup the back of his head, which somehow is even more drenched in sweat, and hold it so that he has no choice but to look at me.

“What’s wrong witchu?” I don’t mean for it to come out harsh, but his eyes tell me it did. “You okay? You hurt?”

“No, I ain’t hurt,” he whispers, his voice still squeaky.

“Then what’s up with you?”

I can see it happen. The ballooning inside him. I can see it pushing at all sides of his body, stretching him from the inside out like bubbles on the surface of Lake Merritt, sitting there, pushing against each other until one bursts, sprays, and returns the surface to the shiny it was before. Trevor is on his way to bursting, his skin betraying him, sending waves of that heavy kind of lonely through the air.

“I just don’t wanna leave.” And it’s like his own words rupture his seams, tears flooding into his sweat.

I take him into me, hold him to my chest. The basketball falls out of his hand and bounces across the pavement. “What you mean, boy?” I whisper into his ear.

His response is half sobs and half words. “Mama ain’t been home and Mr. Vern keeps knocking on our door saying we gotta pay or leave and I been hiding so he don’t see me.” Trevor says he’s been betting to make rent money, but he’s been spending it all on lunch at school, hiding half of his lunch to save for dinner. He trails into deep heaves, and I grip him tighter, so tight I wonder if he’s lost circulation when he stops shaking, his body heavy against mine. His face is sunk and he lets me lead him back up to his apartment, where I leave him on the mattress looking like he’s gonna either fall asleep or burst into tears again.

The flying moments solidify inside my rib cage like a photo album in the body. Trevor and I sweltering, jumping, always close to the sky. Alé and her weed, that smile quick, Sunday Shoes, funeral day. For these moments, I forget my body is a currency and none of the things I did last night make any sense at all. Trevor’s body, the way it fills up with air and releases, reminds me how sacred it is to be young. These moments when all I want is to have my mama hum me a lullaby I will only remember in dreamland.

From Nightcrawling. Copyright © 2022 by Leila Mottley. Published by arrangement with Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.