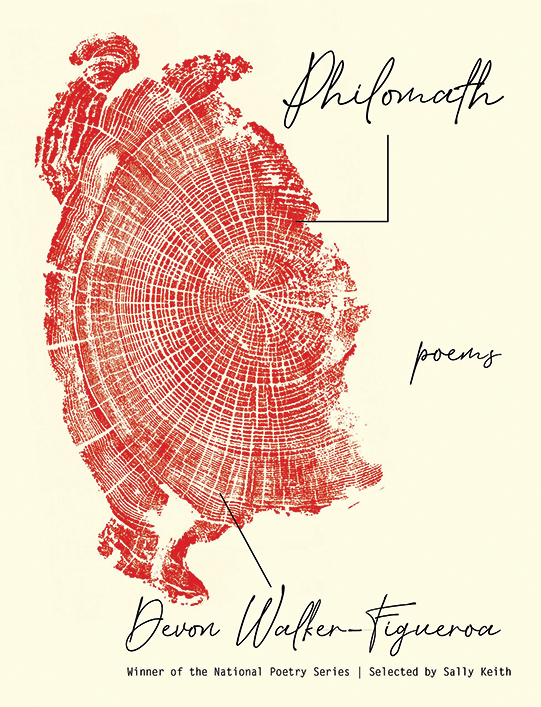

The page was my freeing space to say some truth about shit, to wrestle in the wide berth of freedom it created for me,” says poet Threa Almontaser about writing her debut collection, The Wild Fox of Yemen. Almontaser’s book and the nine other titles included in our seventeenth annual debut poets feature show what can happen when writers wrestle within that freedom. Moheb Soliman reinvents and politically recharges the nature poem in HOMES, while Desiree C. Bailey weaves together songlike poems in quest of a self and freedom in What Noise Against the Cane. Dennis James Sweeney imagines two explorers in Antarctica in his hybrid collection of prose poems, In the Antarctic Circle, while Shangyang Fang attends to the tensions within longing, desire, and beauty in the lyrical Burying the Mountain. There’s the boundary-defying, sprawling chorus of voices in Aurielle Marie’s Gumbo Ya Ya, and the sustained conversation between art, film, and politics in Cheswayo Mphanza’s The Rinehart Frames. Almontaser preserves Yemeni American history with photos and tender, sly poems in The Wild Fox of Yemen, and W. J. Herbert offers whittled-down lyrics and elegies for extinct species and a dying mother in Dear Specimen. In To Love an Island, Ana Portnoy Brimmer marries poems of protest and love for Puerto Rico, while in Philomath, Devon Walker-Figueroa conjures a past life in a small Oregon town. Each of these ten debuts is imbued with a sense that the poet made it knowing, as Bailey says, “that this work is yours, that you are creating it according to your rhythm, your aesthetic.”

The poets all answered the same set of questions about the origins and journeys of their books. Their responses are rich with insight and specifics, revealing many of the struggles and joys one might encounter, from reckoning with painful subject matter and weathering rejections to uncovering the book’s shape and finding a publisher that honors one’s work and person. But in describing what compelled them to begin writing their collections, many of these poets note it is not always easy to explain—that much of the process is not predetermined or even visible to the poet. Fang says, “In the early years, like most, I wrote in unattended darkness.” Walker-Figueroa observes, “Inspiration might be inevitable and often occurs when we aren’t looking or don’t yet feel it animating us.” Herbert adds, “On your particular journey, only you can see how dark the water, how luminous the light.”

While much of what goes into penning a collection might be illegible even to the poets themselves, they all have ideas about what a book can be—a site of awe, a stay against the past slipping away, a space to bear witness and resist, an artifact of the imagination, and/or a blend of “affect, intellect, and being in the world–ness,” as Mphanza says. The ten debuts here inhabit these possibilities and show what comes from building a craft, leaning into “the strange, the wild, the fugitive,” as Marie says, and seeing what poems emerge.

Threa Almontaser | Desiree C. Bailey

W. J. Herbert | Ana Portnoy Brimmer

Cheswayo Mphanza | Shangyang Fang

Aurielle Marie | Dennis James Sweeney

Moheb Soliman | Devon Walker-Figueroa

pw21_almontaser_final_phr.jpg

Threa Almontaser

The Wild Fox of Yemen

Graywolf Press

(Academy of American Poets First Book Award)

The first hope was no bigger than an eyelash,

was born in the middle of war, where we were told prayer

can change the fate of anything. Even dirt.

—from “Operation Restoring Hope”

How it began: It was less a sudden idea and more a gradual obsession with the notion that what has already been said is still not enough. Yemen and South Arabia are always on my mind, and the page was my freeing space to say some truth about shit, to wrestle in the wide berth of freedom it created for me.

Studying writing in college was wonderful. I didn’t know anything about poetry—I was a visual artist. I had read nothing but fantasy and comics. And even the poetry I did read later never felt fully enough, that connective thread that made the poem relatable to the reader was, for me, always half-found. Part of it was simply mustering the courage to be like, “Okay, I need to write this, I just need to write this.” And each poem made my skin a little thicker.

My biggest fear was readers feeling sorry for me or my people. I want them to feel awe, admiration, attentiveness. I was tired of subconsciously internalizing the way the white gaze writes about Yemen in the media and in literature. We’re not all about child brides and camels and bombed school buses. I attempted to write about experiences that have been underrepresented in modern literature because I couldn’t find contemporary work written by an Adeni American of this generation. It makes me sad to know a culture so rich and ancient is hidden in this way.

Inspiration: I see myself as a preserver of South Arabian and Yemeni history in a context where we are not recognized in the Arab American literary world. I’m essentially a research-based poet, so I read a lot of political and anthropological texts on the country. I also visit museums and library archives for photographs from South Arabia’s past times of prosperity and joy, photos with titles such as “Afternoon gathering of neighborhood women,” “In the kitchen before the midday meal,” and “Lewi Faez Studying in His Grandfather’s Jewelry Workshop.” Because I was a visual artist first, I love finding the stories within image-based texts.

Influences: The tribal poets from my village influenced my work a ton. Poetry in Yemen is a tool used to record history. At each birth and death, each victory and tragedy, we call on poetry to do its wordy, ancient magic. It may counsel royalty and even offer diplomatic analysis to political leaders. Arabic, specifically in poetry, delves into new depths with language, so Abdullah Al-Baradouni’s translation effort also empowered and fueled my writing, especially when I engaged with his grammar and music.

Jibran Khalil Jibran’s books showed me a new way of multimodal writing. He mixes parables and fragments of conversations teetering on the philosophical, aphorisms, short stories, and political essays—combinations that explore diverse literary forms, sometimes all at the same time. From him I learned to give myself as a writer the grace to know I’m always capable of change in myself and in my work, even more when imagining the myriad possibilities for myself and where this first book could go. I love seeing bio titles like “poet and photographer” or “essayist and filmmaker.” They’re not constricted about who they might become.

The late rapper MF Doom’s imperfectly perfect loops and rough-sounding vocal takes, coupled with his obsession with cartoons and comics, reminded me to let that childhood endeavor of being an Artist sweep over. It’s a cultural stew I grew up absorbing. Whenever he used words mid-rhyme like Zoinks! that signaled to those who watched Saturday morning cartoons, he really made it fun to confront this book. Hip-hop has a confrontational nature, a hungry pterodactyl tone of voice I hope is projected in my own work.

Writer’s block remedy: Daydreaming a lot. Recording voice notes on my walks when I have to hack out a new idea. I also like watching music videos or short student animations on Vimeo. When I’m struggling to put sentences together, watching other art forms outside of my orbit helps me visualize the strange note or evolved twist I had been trying to put into words.

My writer’s block usually is just me being lazy about the process I know I need to do, sitting and writing this thing I’m trying to make for the long haul. Because it will not satisfy me until twenty-three drafts down the road. So when I’m blocked, that’s me telling myself I don’t have the bandwidth for that long-term relationship with the project right now.

I love revising old work to keep me going. It feels like all of the mysterious stuff that isn’t quite in this realm of understanding is out of the way and I can just sit down and be a person who likes to read, who is reading this thing, and I can figure out what is and what is not satisfying me, what doesn’t sound right when I read it out loud. Or I catch the one line that’s way longer than the rest on the page itching at me. I feel like I have tangible skills I can apply for that. It’s just first making the thing—every time I sit down to do it I’m like, “How did I do this last time?”—and going from there.

Advice: My friendships with other artists, often in different genres, have nourished and encouraged my soul a million times over. Surround yourself with a community of people, whether face-to-face or online, who genuinely want to see you succeed, who celebrate your successes even louder than you do. Disentangle yourself from that vision of success or victory being in the hands of the institution. Ask yourself, “What keeps me lit and lifted?” then embrace those things with your whole chest. Because you can get lost in the hustle proving that you deserve to be somewhere, and that’s very tough work.

Most of all, the advice I wish I’d gotten was to chill out and relax and have fun. Which is super basic, but I was getting some heavy advice from people and I remember just wanting someone to say something light about the whole thing.

Finding time to write: I carve it out during sunrise, so around five or six in the morning. I’ve learned through practice that following the sun is the most generative way for me to write. It’s the reading that I tend to let fall when I get overwhelmed, and it’s reading that later reels me back in.

Putting the book together: I’ve always had three sections in my manuscript, maturing in both narrative and voice the further it got toward the end. I compiled the poems and decided which felt complete and which felt like they were supposed to be a different book. I did it the old-fashioned way, laying all the papers on the floor, my poet gaze roving for recurring images or words, moving the pages around like a jigsaw puzzle until they somehow fit into one body.

What’s next: I’m currently working on a full-length duology about a hijaby boxer and the new kid at school, the exciting and sometimes morally gray ways in which they interact with the world around them. I’ve always dreamed of picking up a story that starred a South Arabian girl who was the apple of someone’s eye, was brave, confident, and grew as a character, and her being hijaby or queer wasn’t the focus. I also very much wanted Muslim teens to get a magical surrealist adventure that so many other teens get to have. I actually first came to write this story because I wanted to read a book where a character didn’t have to get away from their Muslim identity in order to make sense to themselves. These protagonists are neither the perfect human beings setting up unrealistic standards for their age group, nor are they the worst, throwing their culture, family, and religion under the bus in favor of “fitting in.” I also wanted to find more empathy for the immigrant adults in a YA protagonist's life, and to understand what informed their lives and traumas. I tried to write something that is at once a witness to the destructive spirit, while also learning to care for the self. I hope it helps teens dealing with grief to understand, process and validate their own feelings, and for people who live with obsessive thoughts to feel less alone. Essentially, it’s a contemporary story about courage, loss, and generational magic. It navigates love in all of its forms, the loyalty of community, and finding tenderness behind the violence of trying to survive. I’m absolutely stoked to share it with the world soon.

Age: 28.

Residence: Raleigh, North Carolina, and Yonkers, New York.

Job: I used to teach ESL, which I love, but I recently returned to scholarly research.

Time spent writing the book: The fetus form for these poems started in 2017, and I didn’t finish editing them until the week my proofs were due in 2020. That’s where I really felt like I was going into uncharted waters. The e-mail Graywolf sent saying this was the last time I could change anything freaked me out so I decided to give the poems a full metamorphosis. I did things I was afraid to do before. What came from it were my original poems in a range I didn’t even know they could reach, drawing things from unexpected proximities. That final manuscript felt like its own ecosystem. In all, I would say about three years of writing and hard-core revising, but many years before that just learning how to read and write poetry.

Time spent finding a home for it: About a year after I graduated with an MFA, I sent the manuscript to four or five contests, nervous not only about who would take my work, but what kind of home they would make for it. I thought deeply about the company I wanted it to have, and was very intentional—and rightly nervous—when sending it out. During the waiting period, I had to remind myself to celebrate everything. Rejections, acceptances, sending out work, all of it. It’s all a becoming. Then the Academy called to tell me the news about the First Book Award and Graywolf Press, and how proud they were of me.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: I loved Desiree C. Bailey’s What Noise Against the Cane (Yale University Press), Emma Hine’s Stay Safe (Sarabande Books), and Diamond Forde’s Mother Body (Saturnalia Books), just to name a few.

The Wild Fox of Yemen by Threa Almontaser

![]()

Desiree C. Bailey

What Noise Against the Cane

Yale University Press

(Yale Younger Poets Prize)

my goddess is

the wave unsheathing my name

strung through

the conch’s contralto

—from “Chant for the Waters and Dirt and Blade (Slight Return)”

How it began: What Noise Against the Cane came out of the water: the Caribbean Sea that was a large part of my childhood; the Atlantic over which I immigrated to New York; the Atlantic over which my ancestors were trafficked, forced into enslavement to build Western empires. When I wrote the first couple of poems that made it into the book, I was enthralled and inspired by the long global history of Black resistance to enslavement and colonialism—quilombos in Brazil, the burning of plantation crops, the preservation of African spiritual practices, to name a few. I was also trying to make sense of my relationship to place and home as an Afro-Caribbean woman in the United States. I then took a remarkable course with Dr. Anthony Bogues that deepened my understanding of the Haitian Revolution and its centrality to the modern world. I felt like, “Wow, we all owe so much to Haiti and the revolution, and we should all be talking about it, all the time!” In that course I wrote a few poems to think through the role of the ocean and spirituality in the revolution. Those poems eventually became “Chant for the Waters and Dirt and Blade,” the long poem that opens the book.

Inspiration: I had many sources of inspiration in music, art, and nature, but I’ll expand on two here: Kenyan artist Wangechi Mutu’s work and especially the collage painting Beneath Lies the Power, with its sea creatures, bones, and brightly colored birds, was a huge inspiration. I’ve always been drawn to her examination of monstrosity, beauty, and mythology. The idea of collage also informed the construction of the book—the layering of chronologies, places, and voices.

And traditional Caribbean dances like yanvalou from Haiti, which requires you to undulate your body like a wave or a snake, and bélé from Trinidad and Tobago, Grenada, Saint Lucia, and many other Caribbean islands, which incorporates French and West African movements in a dynamic performance of courtship, have also inspired me. The Orisha dances as well. An immense amount of history is carried through these kinesthetic stories. It feels miraculous to move in the ways that my ancestors might have moved.

Influences: M. NourbeSe Philip’s She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks (Casa de las Americas, 1988) has been at the center of my poetic practice for many years. I was introduced to this text in an undergraduate poetry course with poet Mark McMorris. It felt radical and unruly, like my mother’s mother. Here was this Black woman, from Trinidad and Tobago like me, an immigrant like me, writing in the literal margins, layering registers and sources, working through ideas of displacement, colonization, and home. This book showed me how to work through these large questions and movements of my life while experimenting with space and language.

Aracelis Girmay’s the black maria (BOA Editions, 2016), which is such an exquisite offering. I almost want to stop responding to this question so that I can crack open this book right now! Girmay’s rendering of Eritrean history, including the ongoing, perilous journey of asylum-seekers across the sea, and state violence against Black people in the United States is monumental. the black maria allowed me to see the structure of my own book. It showed me how to include different times, places, and stories in one book. It pushed me along as I had my own musings about the ocean and what it has witnessed.

Edwidge Danticat’s short story “Nineteen Thirty-Seven” weaves the history of the Parsley Massacre, the nineteen-year U.S. occupation of Haiti, and the Haitian Revolution while exploring intergenerational trauma, memory, and the bond between a mother and a daughter. It is everything. I teach it whenever I can. I admire how Danticat works with history while never weighing down the narrative or sacrificing lyricism.

Writer’s block remedy: Rest. Reading. Laughing with friends and family. Visiting Trinidad always revives me. Moving my body. Slow wining or twerking in the mirror. Being in the ocean. Honoring my boundaries.

Advice: When you’re writing a book and perhaps submitting individual poems or the entire manuscript for publication, it can feel like everyone but you has power over your work. Resist this feeling as much as you can. Remind yourself every day that this work is yours, that you are creating it according to your rhythm, your aesthetic. That its timing is in accordance with yours and no one else’s. Regardless of how others may or may not receive it, your poems are yours! They already have a home with you, and you’ll share them with the world when the time is right.

Finding time to write: In the past I’ve found it difficult to find time to write due to years of teaching and a nagging feeling that writing was not as important as literally anything else happening in the world. We don’t live in a culture that values introspection and slowing down, which writing requires. Writing workshops really helped me when I first started writing poems. It helped me to carve out space to dream and explore. It held me accountable. These days, I find that creating a ritual or a habit really helps. I get up early in the morning, I light a candle and sit down with a marble notebook and a pen. Some days I don’t write, and that’s okay. I’m not interested in torturing myself.

Putting the book together: The ordering occurred in multiple parts since my book has two sections and a line of text running along the bottom margins. Naturally, the long poem “Chant for the Waters and Dirt and Blade” needed its own section. Since I didn’t write those fragments in order, I organized them with the goal of showing how a person may arrive at the decision to risk their life for the possibility of freedom. I imagined arriving at such a decision to be a tumultuous process for some individuals, and I wanted to highlight the psycho-spiritual complexities involved. I organized the second section somewhat, though not completely, chronologically. Poems that dealt with my younger self are largely at the beginning. I’ve taught many coming-of-age books to my middle-school students and it’s possible that I was inspired by the transformational arc of the bildungsroman. I wanted to show the process of coming into one’s self.

What’s next: I’m writing very loosely at the moment, but thinking about climate, Black people’s relationships to land, uterine fibroids, and Jouvert in Trinidad. We’ll see how—or maybe if—it all comes together.

Age: 32.

Residence: I recently moved from Flatbush, Brooklyn, to Providence.

Job: I’m an English teacher. I experienced serious burnout after teaching in a pandemic, completing an MFA program, and releasing a book at the same time. I decided (or maybe my body decided) to take a few months off from any kind of teaching. I was initially very nervous about this but now it feels amazing to have more control over my time, even if briefly. I may return to teaching of some kind soon, but for now I’m challenging myself to remain open to new possibilities.

Time spent writing the book: It took about five years from the earliest to most recent poem in the book. I took many breaks mostly because of work, health, or a lack of belief in my ability to create this book. I feel very grateful that I completed it.

Time spent finding a home for it: I submitted an early and very different version of this book to chapbook contests in 2015 and 2016. I received rejections. I took a break, worked on the manuscript, and submitted a full-length version in 2018. I received many rejections and continued to work quietly and seriously on my manuscript. When I wrote “Chant for the Waters and Dirt and Blade (Slight Return),” which became the last poem of the book, I knew that everything had finally come together, that the manuscript’s direction was clear. I submitted it to three book competitions in late 2019, and a few months later I got a call from Carl Phillips who selected my manuscript for the Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: I’ve been incredibly moved by Diane Exavier’s The Math of Saint Felix (The 3rd Thing), Isabel Bezerra Balée’s diluvium // a bluejay (Dogpark Collective), Diamond Forde’s Mother Body (Saturnalia Books), Aurielle Marie’s Gumbo Ya Ya (University of Pittsburgh Press), Threa Almontaser’s The Wild Fox of Yemen (Graywolf Press), and Shayla Lawz’s speculation, n. (Autumn House Press).

What Noise Against the Cane by Desiree C. Bailey